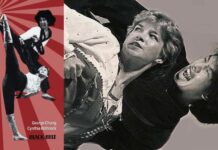

This is A Killing Art Chapter One Excerpt for the book that takes you into the cults, geisha houses, and crime syndicates that made Tae Kwon Do. It shows how, in the end, a few key leaders kept the art clean and turned it into an empowering art for tens of millions of people in more than 150 countries. A Killing Art is part history and part biography — and a wild ride to enlightenment.

CHAPTER 1: Though Ten Million Opponents Might Rise Against Him

The essence of Tae Kwon Do began during a poker game in 1938, the Year of the Tiger, when longing and violence stalked the world. It was the most reckless day of Choi Hong-Hi’s young life. He lived in a small house in the village of Yongwon, in northern Korea, at a time when Japan was crushing the nation like a trap around a fox. The sun had set on the Choson dynasty, but Choi was twenty years old, full of rebellion, and, like most Koreans, refused to forget his past. He had inherited his father’s small, sharp eyes and chin, which usually tilted upwards or cocked to the side, making him look taller than his five feet.

On that day in 1938, he faced his mother under the dim light of a lamp. He was preparing to travel to Japan in two days to complete his education, leaving behind his daughter and a wife whom he had married in his early teens. In Japan, people routinely abused Koreans, but Choi would receive an excellent education there, the first in his family to complete middle school. The trip would be an honour, even though he had to adopt a Japanese name, as the Japanese government had banned people from speaking Korean and was forcing Koreans to change their identities.

Choi’s mother took a thick wad of money from her pocket. “Be careful not to lose this,” she warned. She had worked hard, from dawn to midnight on many days, selling tofu and sewing clothes to save the money. She folded the bills twice, tucked them inside his belt, and sewed the belt shut. But after she went to sleep, Choi went to someone’s house to play Hwatu, a popular Korean poker game. He had been gambling, drinking, and smoking since the age of seven — a partier, like his father. For many years, his father had owned a successful brewery, eventually deserting his wife and taking Hong-Hi and the two other children to live with a kisaeng, a Korean geisha. Living with kisaengs had been an old practice from the Choson dynasty, but it should not have included abandoning the first wife, according to Confucian thought.

The kisaeng had ruined several men’s lives already, but she made an impression on Choi; he thought she was worldly and sophisticated compared to his mother. Choi had been six years old when the kisaeng became his stepmother. Those were the years when he learned how to gamble, smoke, and drink. She was an opium addict and ran a tavern, cooking her excellent food and singing her p‘ansori songs, the classical music favoured by kisaengs. Choi saw how his father could be naive, obstinate, and deeply indulgent — how he gave her everything he had. Finally, his father lost so much money gambling that he sold the brewery. In those early days, the young Choi rarely visited his real mother, who was living in poverty in another part of the village.

One day, he tried to deliver soup to her, but the kisaeng found out and sent a thug to knock the bowl out of his hands. Choi was devastated as he watched dogs lap the food from the dirt. He would never forget that day, not even after the kisaeng died at the age of thirty-eight, when Choi was ten, and his father, as Confucian custom dictated, returned to the first wife. His parents rarely spoke to each other afterwards, and his mother, not his father, raised him for most of his life.

To support the family, the boy helped his mother on their small plot of land, tending the garden, feeding the animals, and making tofu — sometimes on the lookout for his father’s blows, which struck like lightening. The process of soaking, grinding, cooking, straining, and pounding tofu was so intense that for the rest of Choi’s life he loved eating tofu because it reminded him of his mother. As was the custom during meals, his father ate first. Choi’s mother would place rice and side dishes on a table while the family waited. Choi and his brother would peek through a little hole in the door to see if their father would leave some of the rice uneaten, the delicious smell floating into their noses.

But now, at age twenty, Choi would flee all that. In 1938, after his mother sewed the money into his belt and went to sleep, Choi snuck out of the house and met Haak-Soon Huh (a local wrestling champion) and a few friends.

Choi loved the parties that went with poker, and he was excellent at Hwatu. He played so well that he could spot cheaters, which meant that he could cheat with the best of them, but he did not on this day because the others at the table were professionals.

In rapid succession, he and the others laid down the colourful cards and staked their money, but as the game progressed, Choi fared badly. “Strange,” he thought. “I am not winning.” He continued gambling, hoping to win back his losses.

Some of the Hwatu cards have poetic names, such as Crane and Sun, but the poetry may have been lost on Choi as he detached the education money from his belt and gambled more. Soon, he lost all the money that his mother had given him, but he convinced everyone to continue playing. Dawn was still far away, Choi said, and they should wait for him to win back some of his losses.

Finally, the wrestler stood up. “The purpose of gambling is to win money,” he said. “I’ve waited long enough.”

Choi wanted to attack him but knew that would be like a fox jumping a tiger. Choi could fight a bit — at age fifteen he had learned some T’aekkyon, an old martial arts game, from his calligraphy instructor — but the wrestler loomed as a bigger and better fighter. As he sat there, Choi saw a thick bottle of ink on a desk nearby. I wonder if he pictured the next few seconds in advance: the way the room blackened before his eyes, the way the wrestler put the money in a pocket, the way Choi’s hand found the bottle of ink, and the way it sailed at the wrestler. The bottle smashed on his forehead — a lucky hit. The wrestler fell on his back, blood and ink trickling down his face. While the other gamblers watched, Choi walked to the body, pulled the money from the man’s pocket, counted what he had lost, and fled. No one stopped him, perhaps because they knew the wrestler would hunt him down.

Choi rushed home, cold and sweaty, and wondered if he had murdered the man. All that blood! What would his parents do? He and his brother and sister had always obeyed their father, who had studied the works of Confucius and become a doctor of Chinese medicine before opening his brewery. Their minds were laden with obligations and traditions, a Confucian legacy so warped that Choi’s grandmother kept her nail clippings because respect for parents meant respecting every part of one’s body.

But non-Confucian values — those of the heart — thrived in Choi and his era, values related to superstition and intuition, freedom and insight, passion and drunkenness. In Choi’s household, obedience lived beside rice wine and geisha girls, and attacking a man after losing a poker game would create intolerable trouble for his parents.

As he walked home after the poker game, did he remember the first time he had created trouble for them, his birth in 1918? That was the Year of the Horse and a year in which the Japanese government arrested, tortured, or killed 140,000 Koreans who were suspected of resisting the Japanese empire. It was a year when cunning and independence were at the centre of the world. Choi was born a runt and looked destined to die young. His mother came from a wealthy family but hated her husband. Each time she gave birth, she left him to bring up the newborns in her father’s comfortable, Confucian home. But her father treated her like a servant because daughters, after marriage, were not supposed to return to their parents. She bore the humiliation for the sake of all eight of her babies, only three of whom lived past the age of two. She would grumble later, “After the greater ones are all gone, the worst weakling survived to give me a headache.” Choi, the weakling and the youngest, was sickly and short for the first four years of his life. In desperation, his mother tugged his legs night after night as he slept, trying to make him taller.

As Choi left the poker game, he wondered if the wrestler was dead. Afraid of his own parents, he avoided home, the police, and the entire town. He walked sixteen kilometres past cow-driven carts to a train station, traveled twenty hours on a train to a Pusan port, and caught a ship to Kyoto, Japan. That day marked him; for the rest of his life, he would embroil himself in conflict then flee.

Months after arriving in Kyoto, Choi met a man from his village who told him that the wrestler had recovered and was counting the days to Choi’s return. Choi felt doomed and began training in Shotokan Karate to defend himself. Karate was a Japanese martial art that Gichin Funakoshi had transferred from Okinawa to Japan in 1922. Choi had watched a class and concluded that it was devastatingly powerful; it aimed punches right to the heart, solar plexus, or whatever vital spot could lead to death.

Beginning in 1938, Karate strengthened a trait in Choi that Westerners associate with Japanese kamikaze pilots from the Second World War or with samurai warriors from a thousand years ago. Choi called it Indomitable Spirit: “A serious student of Tae Kwon Do will at all times be modest and honest. If confronted with injustice, he will deal with the belligerent without any fear or hesitation at all, with indomitable spirit, regardless of whosoever and however many the number may be.”

But Choi did not practise Karate for long. He did train diligently for a few years in Kyoto, keeping the wrestler in mind, but he later claimed to have attained a second-degree black belt. Experts dispute this claim, saying that no one in those days could reach that level in such a short time, considering Funakoshi’s standards. In fact, only one Korean, Wok-kuk Lee, attained a second-degree black belt in Karate during that era. Choi likely exaggerated his rank, but he kicked wooden street poles, punched sand to toughen his fists, and trained so much that he failed his first year in middle school, which he thought was yet another reason to avoid going home.

The Karate also proved useful in Japan, where people insulted him and his Korean friends, told them they smelled like garlic, physically attacked them, and treated them like servants. Choi was constantly getting into fights. He was not special in this regard; Japanese bullies had been abusing Koreans for decades, and the nation of Japan had been trampling Korea since 1894. One of Choi’s fights began after he warned two boys to stop bullying a friend. The boys took the warning as a challenge and followed Choi after school. As they approached him, he hit one in the face. The boy fell, and Choi immediately pinned him to the ground with a foot on his neck as the boy’s wooden sandals flailed in the air. The second boy ran away, and Choi released the first, marveling at his new-found power.

Scared of the wrestler and his parents, Choi stayed in Japan for four years, never visiting his village, telling his parents that he was too sick to travel. He saved money and sent it to his mother. At the age of twenty-four, however, after finishing