Chotoku Kyan was probably the most influential of O’Sensei’s Tote instructors and Chito-ryu is abundant with Kyan influences. We can see this in numerous kata that we do, including Bassai, Chinto, Sanshiru and Kusanku. Chito-ryu also has a variation of Kyan Seisan. However, our Seisan is also very close to the common Matsumura Seisan and Kyan’s influence on O’Sensei’s Seisan isn’t fully understood. O’Sensei also learned Ananku and Gojushiho from Kyan.

Kyan spawned over half a dozen popular styles which have splintered into many more groups since his death. Because of this, Kyan is considered not only one of the main influences of Chito-ryu, but of Shorin-ryu as a whole. Like most famous masters, Kyan also attended the “Meeting of Okinawan Masters” in Oct. 25th, 1936 to discuss the re-naming of Tote-jutsu to Karate-do.

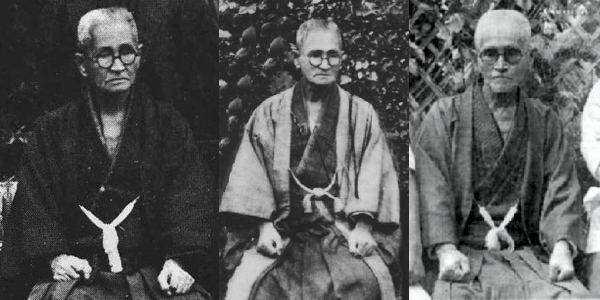

Because of his permanent squint and small spectacles, Kyan was known throughout his life as Migua Chan (small eyed Kyan – Chan is the original pronunciation, it is sometimes pronounced Kiyabu or Kiyatake in modern Japanese). Chotoku Kyan was a weak, sickly child who overcame his poor eyesight and small size to become a renowned master through constant practice.

Born in December of 1870, Chotoku was the third or fourth son of Chotoku Kyan , steward to the Ryukyuyan King Shotai and 11th generation successor of the Shosei family line. Chofu was educated in Chinese and Japanese classics and a skilled martial artist. He was a trusted member of the Royal staff and carried out all the business of the Royal family. Around this time, events that eventually became known as the Meiji restoration were effecting all of Okinawa, especially the royalty and their workers. The Meiji government of Japan officially abolished all royalty and aristocracy in Okinawa in 1872.

King Shotai was eventually forced to leave Okinawa, travelling to Tokyo in 1879. He continued to live an aristocratic life for a while, even bringing some of his more trusted staff including his steward Kyan Chofu. Chotoku accompanied his father to Tokyo at the age of 12 and received an education in Chinese classics until age 16 when they returned to Okinawa, Chofu’s duties to the king concluded.

As a boy, Kyan was small and in poor health. His father believed that Kyan must improve his health to become a proper member of the Shosei family line. Chofu often took Chotoku outside on cold winter days to exercise in various martial arts, including Tote. Chotoku’s father gave him advice on how to train and practice which Chotoku often repeated to his own students years later including the most famous, “Proficiency in karate doesn’t depend on natural talent and ability, but on constant practice.” When Chotoku was about 20, his father felt that he should practice Tote regularly.

Three of the most famous masters at that time were “Bushi” Matsumura Sokon (of Shuri), Itosu Anko (of Shuri), and “Peichin” Oyadomari (of Naha). According to Nagamine Shoshin, Chofu asked all three to train his son.

It has been repeated that Kyan studied under Itosu, Bushi Matsumura’s most famous successor, however, there are other students of Kyan (Nakazato Joen) and even the successor of Itosu Anko (Chibana Chosin) who said that Kyan never practiced under Itosu. There is no way to know for sure without someone uncovering further documentation in the future. Regardless of this, Kyan obtained an impressive Tode education under the very best Okinawan masters.

The Meiji restoration hurt the Kyan finances and they eventually moved to Yomitan village where they owned property. They struggled from then on and Chotoku took on odd jobs like raising silk worms and pulling carts. According to Nagamine Shoshin, Kyan’s adult life was miserable and poverty stricken. Despite this, he continued to train while in Yomitan and learned the Kusanku kata from a Tote expert named Yara Chantan (b. 1816).

Kyan advanced rapidly and by the time he was 30, he was well known for his martial arts skills. Having studied with an unusually large number of experts, Kyan accumulated what was considered a very large number of kata. Here is a list of Kyan’s kata curriculum:

Seisan, Naihanshi and Gojushiho from Bushi Matsumura

Kusanku from Yara Chantan

Passai (Bassai) from Oyadomari Kokan (1827-1905)

Chinto from Matsumora Kosaku (1829-1898)

Wansu from Maeda “Peichin” (a student of Matsumora Kosaku)

Ananku (sometimes Ananko) from a Taiwanese in Okinawa or from a trip to Taiwan, no one knows for sure.

Tokumine No Kon (a bo kata) from the banished official named Tokumine “Peichin”. From “Okinawan Karate” by Mark Bishop, Nakama Chozo mentioned that when Kyan visited the southern island of Yaema, Tokumine had already died. The story goes that Tokumine had taught his landlord the kata and the man kindly agreed to teach it to Kyan.

Matsumora Kosaku, Oyadomari Kokan and Maeda Peichin were well known masters of the Tote taught in and around Tomari village. While similar to the Tote taught in Shuri, Tomari’s Tote had some different kata and a unique flavor. Because of this, Kyan is known for passing down Tomari Tote from these three Tomari greats, although in a modified form. Kyan’s Chinto, Wansu and Passai reflect Tomari style Tote.

Kyan took part in some of the very first demonstrations along with other famous masters following the 1917 demonstration by Funakoshi Gichin and Matayoshi Shinko in Kyoto, Japan for the Dai Nippon Butokukai (founded 1895, The Butokukai is a governing body for Japanese martial arts). Kyan was also a member of the 1918 Ryukyu Tote Kenkyukai (Okinawan Karate research club) founded by Miyagi Choyun and run by the successors of the last generation of masters.

Known as an innovator, Kyan contributed much to the body of Tote knowledge. He was small and had to adjust his skills to his small stature. This led to innovations in taisabaki, kicking and jumping techniques. He never backed up, but preferred to move forward at a diagonal when defending. As with other youths of the time, Kyan took part in challenge matches to test his skill and according to his students, he was never defeated.

Part 2 of this article will appear in the next issue of Zanshin.

By: Travis Cottreau

References:

Hokama, Tetsuhiro: “History and Traditions of Okinawan Karate”, translated by Cezar Borkowski, printed by Masters Publications, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, 1996.

Nagamine, Shoshin: “The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do”, Published by Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1976.

Bishop, Mark: “Okinawan Karate: Teachers, Styles and Secret Techniques”, A&C Black Limited, London, England, 1989.

Borkowski, Cezar: “Nagamine Shoshin, The Living Link to the Golden Age of Okinawan Karate Part I”, Steve Grayston’s Martial Arts, No. 40.

Borkowski, Cezar: “Nagamine Shoshin, The Living Link to the Golden Age of Okinawan Karate Part II”, Steve Grayston’s Martial Arts, No. 43.

Sells, John: “Unante, the Secrets of Karate”, John Sells and Hawley Publications, 1996.

Sells, John: “Chito Ryu Karatedo, the Legacy of Chitose Tsuyoshi”, Bugeisha Magazine, issue #2, March 1997. Maai Productions Inc., PA, U.S.A.

Sells, John: “Seibukan, the Shorin-ryu Karate of Shimabukuro Zenryo”, Bugeisha Magazine, issue #5, Winter 1998. Maai Productions Inc., PA, U.S.A.