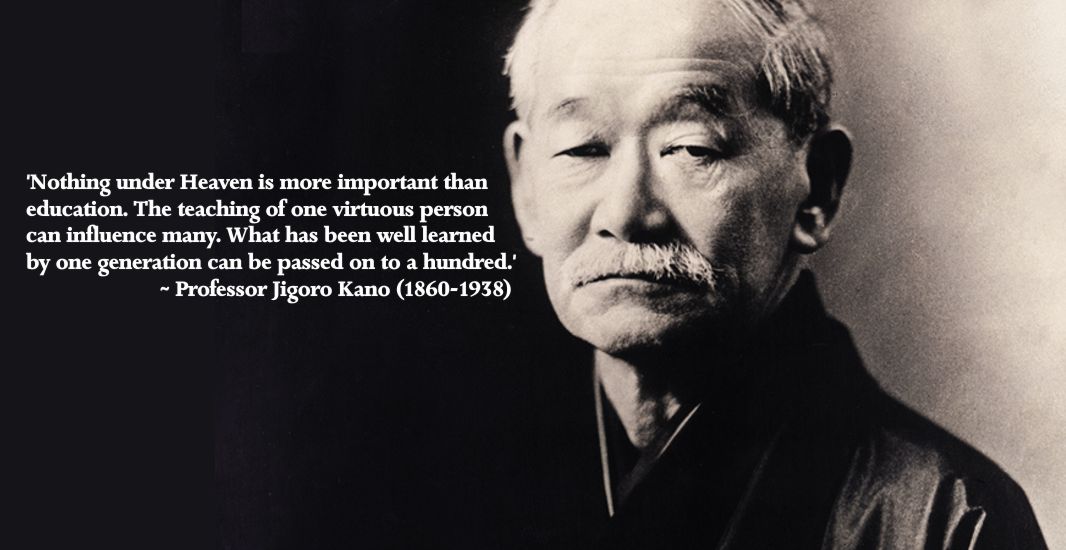

‘Nothing under Heaven is more important than education. The teaching of one virtuous person can influence many. What has been well learned by one generation can be passed on to a hundred.’ ~ Professor Jigoro Kano (1860-1938)

Kano, a famous educator, also made the following comment with regard to judo instructors: ‘They (judo instructors) should, moreover, be able to comprehend how one man is able to gain advantage and win in a contest and how another is defeated. They need to have detailed knowledge of physical education, teaching methods and have a thorough grasp of the significance of moral education. Finally, they must understand how the principles of judo can be, by extension, utilized to help one in daily life and how they themselves can be of benefit to society at large.’

If a student has respect for his teacher, he usually does well in his studies, be it music, mathematics, sport or whatever. On the other hand, if he dislikes his teacher for some reason, he generally does less well. Thus for the student’s success, much depends on the maintenance of a friendly teacher-student relationship.

Be that as it may, all teachers have the important moral responsibility of leading and guiding the young in their pursuit of worthwhile knowledge within the context of a physical, social or cultural setting. The teacher is also expected to safeguard the welfare of his charges while they are under his supervision in classroom study, in a musical studio or in physical activity in a sports’ environment. The ideal teacher is, moreover, one who is able to motivate students in order to help them develop competence in their methods of study and in their adoption of a positive attitude. If these goals are met in full, the student should be able to improve his academic performance, embrace an active lifestyle and perhaps most importantly, acquire a life-long enthusiasm for learning.

I believe that there is a difference between a teacher and an educator. One of the great difficulties for all in the teaching profession is this: How do you teach under-achievers who have no wish to learn? There is only one sure way that I know of and that is to inspire the student with a burning desire to learn. It is only then that the student will, for the most part, teach himself. There are two ways to drive a donkey, one is by judicious use of the carrot and the other is by use of the stick. Of these two methods, the use of the stick will result in the student perhaps making some effort, but at the same time he will probably harbour strong resentment; therefore the carrot or some other potent inducement is needed. Once the teacher is able to inspire the student in some way, he then becomes, in my estimation, an educator, because inspiration usually works like magic. The problem is, of course, what is the best way? A method that successfully stimulates one student may well repel another. The following is a case in point that I heard of many years ago. A Japanese lady called on a distinguished professor of music, who was already in retirement, and asked him if he would teach her young son to play the flute. The professor explained that since he was retired, he no longer gave instruction. Several weeks later, the lady, undeterred, this time accompanied by her young boy, again called on the professor. She once more repeated her request. The professor turned to the boy and said: ‘Do you really wish to play the flute?’ Because the boy seemed to be keen, and his mother so insistent, the professor finally relented and agreed to give him one lesson a week.

The subsequent week, the boy, as instructed, knocked on the professor’s door expecting to receive his first lesson. The professor came to the lobby and greeted the boy. He told him that there were many leaves on his garden and that he should leave his flute in the lobby, get the broom and sweep up all the leaves. The professor returned to his study. Some thirty minutes later the boy again knocked on the door and told the professor that he had cleared the leaves. The professor checked to see that all the leaves had indeed been cleared and said, ‘That’s good. Take your flute, you may go home now.’ For a further two weeks the boy repeated the same chore and returned home with his new flute case still unopened. On the fourth occasion, when the boy had cleared up all the leaves, the professor came to the lobby with his own flute and played two or three pieces. The boy stood and listened intently, by this time no doubt yearning to be taught. But yet again the professor said, ‘You may go home now.’ The next week, however, the professor informed the boy that he had no need to clear the leaves and invited him in and gave him his first lesson. The professor continued to do so for some time, following which the boy became an accomplished musician.

Trevor Pryce Leggett (1914-2000) in similar vein related this concerning a British actress. ‘Edith Evans (1888-1976), one of our greatest actresses, was rejected by teachers at an important drama school at her first hearing. In her reminiscences she says: “Yes, they gave me a hearing. And then they told me, well, no.” But she became a genius at acting. If she had accepted the limitation which they thought she had, it would have been a great loss.’

Another example, again from Leggett, who was a 5th dan shogi (Japanese chess) expert, he related as follows: ‘I knew very well the famous shogi champion Yasuharu Oyama (1923-1992). Chess is a much more popular game in Japan than it is here in the UK, and the chess champion is as big a national figure as a football star here in the UK.

‘When Oyama was a small boy, he got the idea that he wanted to play and went to a famous dojo training hall in Osaka. The head instructor a man of enormous experience who had trained many champions gave him a few test games. He told him: “My boy, you haven’t got the talent for it. To take you on as an apprentice wouldn’t be honest, and it wouldn’t be fair to you. You haven’t got the basic gift for this – go and try something else.”

‘Oyama, the little boy, wept, finally the head instructor said: “Look, I’m not taking you on as a pupil, because that would not be fair to you. If you like, after school you can come here and you can help clean up, as a servant. You can watch the games and you may play occasionally, but I’m not taking you on as a student. It would be wrong and would just give you false hopes.” ’

The result was this: Yasuharu Oyama soon became a chess genius. He achieved professional status in 1940 at the young age of 16. He went on to totally destroy all opposition and dominated Japanese chess for 25 years, winning over 100 major competitions (1,433 games in total) during his long reign.

Both of the above-mentioned examples are similar in that both teachers seemed to know instinctively that the boys had potential. All the teachers had to do was to consider the best ways to inspire them. Their methods were different and perhaps a little eccentric; nevertheless both teachers achieved their objectives. Thus, there are many ways to skin a cat.

After the collapse of Japan’s feudal regime in 1867, most samurai became unemployed. Those who were involved in budo, however, campaigned to have martial arts introduced into the Japanese school system. The ministry of education authorities rejected their appeals as being impractical. There were not enough budo practitioners qualified to teach so many classes nationwide. There were few dojo facilities on school premises. Budo training was considered by many as being too rough and therefore hazardous for children to engage in.

Had it not been for prominent educator and judo founder Jigoro Kano, participation in kobudo (traditional martial arts) would have probably remained an unpopular, dying pastime. Kano, however, was impressed with the western concepts of physical education, and had the idea that through teaching children physical education and modern-day budo, strong bodies and ethical, eager-to-learn minds could be developed and in future be of value to society. From the 1890s Kano’s articulation concerning judo’s significance in education became very influential, so much so that other budo practitioners followed his example. Kano taught the physical principle that by use of judo; it was possible for a small man to defeat a bigger man. But for Kano there was a far more important deep ethical meaning.

Kano seemed to believe that by emphasizing student’s mental development through judo training, it could go some way in mitigating what he saw as the moral decay of Japanese society.

Kano seemed to believe that by emphasizing student’s mental development through judo training, it could go some way in mitigating what he saw as the moral decay of Japanese society. By being angry with political leaders for this decay and harboring a bad attitude did not help matters, one merely wasted one’s energy thus opposing judo’s goal of using energy most efficiently. In his writings he advocated that wanting to do good for society is not sufficient, the young especially should acquire the habit of actually doing good. He considered the fruits of physical education for the young would enable them to make a useful contribution to the betterment of society. Kano was against the practice of engaging in judo solely for the purpose of winning medals. He believed that judoka should also foster personal spiritual development.

The outcome of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 convinced many Japanese politicians of the practical benefits of adding budo training to the Japanese school system. Thus, by cultivating strong bodies and a martial spirit, the young could better serve the nation. Therefore, by 1918 budo had been approved as a subject and added to the curriculum of Japan’s middle schools and included as an elective subject for the nation’s primary schools. As expected, by the 1930s there was a strong sense of military spirit, discipline, and loyalty permeating the country nationwide. These core beliefs, I believe, were instrumental in persuading the authorities to make budo training compulsory for many Japanese school children. However, in 1945, after the Second World War defeat of Japan, the US-led occupation forces quickly issued a nation-wide ban on budo training at all schools. Thus, budo, mainly judo and kendo disciplines, were not re-introduced to the school system until after the occupation forces had left Japan in the 1950s.

Turning now to modern-day judo, much depends on the attitude of the student when the instructor is asked to decide whether to accept him for training or not. Sometimes a father will bring his son to a judo club and ask the instructor to teach his boy. Often the father has the desire for his boy to learn judo, but that does not necessarily presuppose that the son has, too. Quite often, in such a case, the boy is not really committed, soon loses interest, and quits training. Conversely, should a boy visit a dojo of his own volition and enroll himself, the outcome is somewhat different for by coming alone the boy indicates that he is eager and has a genuine wish to learn judo. Usually such a boy tends to train in a diligent manner and makes satisfactory progress.

When it comes to teaching the art of judo, the main priority for the instructor should be to take every possible precaution to avoid student injuries. If children are injured while practicing, their parents will no doubt take a dim view of judo, consider it to be a dangerous activity, and perhaps forbid their child from further participation. In most sportive activities, of course, accidents and possible injury can happen. However, since judo is a non-violent activity and provided training is carried out under strict and experienced supervision, injuries should be of rare occurrence.

Judo instructors can have a significant influence on the young. Their effect can continue long after the student’s judo career ends. This implies that instructors have a moral responsibility to stimulate their charges in a positive manner; however, will this be for good or ill? And, what determines the nature of an instructor’s authority over his charges? There are a number of forces at play, but the primary one for consideration is the personality of the instructor. Instructors should endeavor to become moral exemplars. They should be persons of suitable character, displaying moral courage, compassion, humility, respect, honor and integrity. These are indeed all demanding traits. Of course, an instructor values his students’ winning championships, but some students seem to mistake sport for war and believe victory is all that matters. More than victory; winning in an honorable way is what matters, by having respect for oneself, and safeguarding the reputation of judo also matters a great deal. Surely it is better to lose with honor rather than win without it. Once accepting the role of instructor, one also needs to accept responsibility for attainment of excellence of character in those whom they teach.

My hope is that more instructors will take this responsibility to heart and seek to be role models for the young. If instructors are truly sincere in this regard, they can exert a favorable bearing on the lives of their students that may last a lifetime. Thus, instructors have an incredible opportunity to use their celebrity power to influence positively the next judo generation.

Lastly, teaching the young to think for themselves and drawing out the natural talent that many of them possess is always a worthwhile objective. Judo should not be considered an end in itself, for it can also be educative if approached in the spirit that professor Kano intended. Judo instructors should never deviate from the above-mentioned high principles of their calling. For it is only then that they will be able to bring lasting HONOR not only to themselves but also to the repute of the judo fraternity worldwide.

References:

The Spirit of Budo, Trevor Pryce Leggett, Simul Press, Tokyo, 1993

Judo Memoirs of Jigoro Kano, B.N. Watson, Trafford Publishing, 2008, 2014

Memorias de Jigoro Kano, (Portuguese) B.N. Watson, Editora Cultrix, 2011

The Father of Judo, B.N. Watson, Kodansha International, 2000, 2012

IL Padre Del Judo, (Italian) B.N. Watson, Edizioni Mediterranee, 2005