As the Arizona night descended around us in a blanket of warm desert hues, the yellow light from a kerosene yard lantern danced across the soft eyes of Teruo Chinen, reflecting in them the Chinese blood line of his Okinawan lineage, of which he spoke proudly. He talked about his life in Okinawa, Japan and the United States, karate, Goju Ryu, Miyagi, China, Kung Fu, ancient Chinese Generals and an evening’s worth of other subjects related to his lifetime of training and teaching his Okinawan martial art to anyone who would pay attention.

A cluster of mostly adult students sat listening quietly, absorbing the thoughts and feelings of this man who, because of his nationality and heritage, embodied for them the history and spirit of that art which they pursued. As the evening passed the students randomly stood to leave and were handed a certificate to commemorate the weekend. As the twenty or so people bowed goodbye and accepted the piece of parchment, Chinen mentioned each one’s name and acknowledged something unique to their weekend’s training. They smiled and bowed again, appreciating the fact that this teacher, whom most only had met for the first time two days before, made the effort to learn their names and take interest in a brief moment of their particular lives.

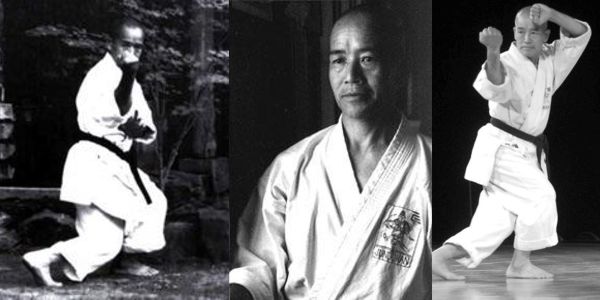

The spectrum of karate teachers in the world today covers a range that includes on one end a vast array of politicians – men and women who shake hands, pass out certificates and make money. On the other end exists a few who actually practice karate – that is punch and kick, and repeat endless kata. The political side is inhabited by mouthpieces who claim rank, pat each other on the back, make speeches, push for Olympic acceptance and grow soft and fat. The other end is inhabited by a handful of teacher-students, who spend most of their time sweating on a dojo floor, actually working at becoming the “masters” that so many politicians would claim to be. Out on the far reaches of that latter rarefied end stands Teruo Chinen, to many the embodiment of what karate might have represented during its five centuries of Okinawan life – a hard muscled, quiet, teacher who still practices his art daily, even after the better part of 60 years.

As you listen to him, one of the things you notice is that Chinen, unless prodded, doesn’t mention politics or position, his rank or that of anyone else. He talks only about the history of karate or how to become better at it, and continually admonishes the ones who do listen to practice harder. If the term “master” refers to a person who practices an art until they have completely absorbed it, then Teruo Chinen probably deserves the accolade, although he would never claim it.

In the political sphere, there are those who wouldn’t agree. Mr. Chinen is not a very good politician and has his share of detractors. That doesn’t seem to matter to him and he is a man dedicated to his life’s pursuit more than most people alive today, especially among his contemporaries. At 62 most teachers rely on their reputation, warranted or not. Chinen still works out regularly and, when he takes off his jacket to demonstrate Sanshin for a writer, the density of his muscles and the flow of his movement prove the fact.

Chinen was born in June of 1941, seven months before Pearl Harbor, in Kobe Japan. His father, a seaman in the Imperial army, died on a suicide ship in 1944. Somewhere between Guam and Tokyo the boat’s captain decided that he and his men should go down together in glorious ritual mass death rather than surrender to the American military. An American gunboat dragged two sailors from the murky waters to tell the story to the family.

At war’s end Chinen returned to Shuri, Okinawa with his widowed mother and a half dozen siblings to a ruined country and a two-room house with a canvas roof that belonged to his uncle. His mother found work at an American air base. Because his uncle was a policeman, this meager residence, more than most Okinawans had at the time, sat in the middle of a police residential area and, as destiny would have it, three doors away from Chojun Miyagi, a Hancho in the police department.

Chinen remembers being in Miyagi’s dojo as a wide-eyed boy of 7 or 8, with Miyagi, fatally ill and overweight, directing class from a chair. He also remembers standing in the street in 1953, watching Miyagi’s coffin being carried through the neighborhood on an American army truck, and the Okinawan policemen snapping a salute as the body passed.

He remembers when it was all over, helping carry the makiwari, chiishi, kongo ken and other training implements from Miyagi’s house to the new dojo that his student Miyazato started and named the Jundokan. And he remembers studying there with a dozen or so other adults and children, trying to put together the style that Miyagi had taught them and had intended them to pass on.

There were other Miyagi students senior to Miyazato. Chinen believes that Miyagi appreciated the fact and planned for it. To Yagi, the most senior, he bequeathed his robe and sash, the “flowers” of his training, commemorating the years the man had dedicated to learning the art. To Miyazato, the karate “soldier”, he bequeathed the training implements, the “seeds” of the art, knowing that Miyazato would carry on the training and pass on the art. And he did. Some are of the opinion that much of what Goju Ryu has become in modern times is as much due to Miyazato’s influence as to Miyagi’s.

After Miyagi died, Chinen continued to study off and on in Miyazato’s dojo for another 6 years, earning a black belt (with no certificate) and learning the kata that tied together the bunkai he had been practicing since he was a child. The bunkai, is the meaning of the kata moves and Chinen says that he learned the bunkai first, and that only after he had learned the basics was he shown the kata that embodied them. In other words the meaning of the moves and their application – the ability to fight – was the primary pursuit in those days in that dojo, and the kata were more or less a way of remembering them. Consequently the individual kata have much less importance for him than for many karate students and teachers who often judge their own prestige and position by the number and rarity of the kata they have been taught. Chinen relates the kata to the tip of the iceberg, and the bunkai-oyo to what lies underneath. Most of us spend most of our time polishing the tip for tournaments and tests and never plumb the depth of the art.

At 19 Chinen decided to pursue an education in Japan proper and with his Okinawan passport in hand, traveled to Naha to board a passenger-cargo ship with pounding pistons and piles of boxes. He sailed 18 hours to picturesque Kagoshima on the southern tip of the Japanese mainland. There he found a train to Osaka where he stayed with an aunt for a couple of months and then on to Tokyo and a Shotokan dojo in a section of the city called Yoyogi, where his sempai, Morio Higaonna, already taught Goju Ryu on odd nights. Chinen remembers learning to spar Japanese style and “the little Goju boy from Okinawa”, as he referred to himself, getting the snot knocked out of him by the Japanese tournament competitors. Unlike many Okinawans, however, he sees sparring as an aid to training rather than a hindrance.

Chinen stayed in Yoyogi for a couple of years trying to work at a college degree and then made a trip almost around the world visiting various Goju dojo throughout Europe and Asia, and finally ending up once again in Okinawa at the Jundokan in 1972, sleeping in a dinky room above the dojo and training with Miyazato. This time he only stayed 3 days and when it was time for him to leave Miyazato called upstairs.

“Chinen!” he said.

“Hai, Sensei.” Chinen answered.

“Stop down before you leave.”

“Hai, Sensei.”

Chinen packed up his few belongings and went downstairs.

“You’re teaching in Tokyo, right?” Miyazato asked.

“Hai, sensei”

“Here, take this.” And Miyazato handed him a black belt. “How about fourth degree.”

His only other promotion came during Miyazato’s visit to the United States in the late 1980’s, shortly before the teacher’s death.

“How old are you, Chinen?” he asked.

“Fifty, sensei.”

“You’re teaching, right?”

“Hai, sensei.”

“Here.” And he handed Chinen a certificate for 7th degree.

“Thank you, sensei.” Chinen said.

Those were Chinen’s promotions.

It is a bit ironic that Chinen ever even pursued a career in Goju at all and received a certificate from Miyazato. His family, his uncles and cousins, are well known for their dedication to Shorin Ryu. One ancestor, in fact, was Masami Chinen, the famed originator of Yamani Ryu Kobudo.

Chinen came to Spokane, Washington in 1969 to take over a dojo. The deal fell through when he got there but he soon found work teaching at Gonzaga University and several community colleges around the area. He teaches there still.

It is obvious when you watch him that Chinen is a professional teacher. He keeps the class both motivated and interesting. He teaches the technique, the philosophy and the history of karate, as well as the history of the ancient Okinawa and China that engendered the art.

One thing that strikes an observer is how well Chinen speaks English. He explains in detailed proper grammar the depth of the art he is presenting, even using slang and argot – correctly.

Nowadays Chinen spends most weekends traveling around the United States and the world giving seminars to Goju Ryu schools as well as to a variety of others. The particular one where this interview took place was a Wado Ryu dojo in Tucson, Arizona. Chinen doesn’t care about the politics. It’s all karate to him. In fact he has taken to often referring to what he teaches as Kung Fu, rather than karate or Goju, believing that Okinawan karate is simply the flow-through of the Chinese art, and, since the words “Kung Fu” more properly refer to someone who is working to master an art, (any art from wood working to computer programming -the words literally mean “work master”) it reflects his belief in the benefits of perspiration over politics.

Chinen represents a philosophy. That philosophy is that the art of karate is to be practiced diligently, and if practiced diligently, will offer an understanding that only comes from such dedication, an understanding of technique and application – of life and death. It’s the rare individual who continues to practice karate throughout a lifetime. For many it’s simply too much work. Most become content with the trappings of rank and position, thinking that somehow a black belt or a title is a goal, forgetting that anything given out by man is suspect. In the end the only truth one can hold onto is the truth of work, and the master. The only real path to enlightenment comes from within. Teruo Chinen has a good chance of finding that out.

With the kerosene lantern consuming its final fuel and the Arizona night completing its warm descent and with most of the students departed, the evening’s discussion faded into quiet reflection. Chinen peered off into the darkness for a long second, as if waiting for some motivation to speak. The silence grew in the soft evening and, then, as the fingers of light danced across his Chinese eyes, he turned with a quiet smile and summed it all up.

“I’m a very happy man.” He said.

Teruo Chinen passed away on September 9, 2015, in Spokane, Washington.