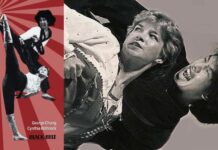

The Education of a Humanitarian, the Making of a Navy SEAL

The Education of a Humanitarian, the Making of a Navy SEAL

“Meet my hero—Eric Greitens. His life and this book remind us that America remains the land of the brave and generous.” — Tom Brokaw

Like many young idealists, Eric Greitens wanted to make a difference, so he traveled to the world’s trouble spots to work in refugee camps and serve the sick and the poor. Yet when innocent civilians were threatened with harm, there was nothing he could do but step in afterward and try to ease the suffering. In studying humanitarianism, he realized a fundamental truth: when an army invades, the weak need protection. So he joined the Navy SEALs and became one of the world’s elite warriors.

Greitens led his men through the unforgettable soul-testing of SEAL training and went on to deployments in Kenya, Afghanistan, and Iraq, where he faced harrowing encounters and brutal attacks. Yet even in the deadliest combat situations, the lessons of his humanitarian work bore fruit. At the heart of this powerful story lies a paradox: sometimes you have to be strong to do good, but you also have to do good to be strong. The heart and the fist together are more powerful than either one alone.

“If you’re restless or itching for some calling you can’t name, read this book. Give it to your son and daughter. The Heart and the Fist epitomizes — as does Mr. Greitens’s life, present and future — all that is best in this country, and what we need desperately right now.” — Steven Pressfield, author of Gates of Fire

“Vivid and compelling . . . a great read.” — Washington Times

A Hudson Booksellers Top Ten Nonfiction Book of the Year

A USA Today and Publishers Weekly Bestseller

A Note from the Author  As a kid growing up in Missouri, I loved reading stories about heroes like King Arthur, George Washington, and Pericles. Their lives were full of action and courage, and I wanted to capture that same sense of adventure in my own life. As I grew older, great mentors and friends have shown me that the path to adventure and purpose can be found in a life of service to others.These friends and mentors have come from many different backgrounds. I’ve been blessed to work with volunteers who taught art to street children in Bolivia and Marines who hunted al Qaeda terrorists in Iraq. I’ve learned from nuns who fed the destitute in Mother Teresa’s homes for the dying in India, aid workers who healed orphaned children in Rwanda, and Navy SEALs who fought in Afghanistan. As warriors, as humanitarians, they’ve taught me that without courage, compassion falters, and without compassion, courage has no direction. They’ve shown me that it is within our power, indeed the world requires of us — every one of us — to be both good and strong.I hope the stories recounted in The Heart and the Fist will inspire you as these people have inspired me. They have given me hope and shown me the incredible possibilities that exist for each of us to live our one life well. –Eric Greitens

As a kid growing up in Missouri, I loved reading stories about heroes like King Arthur, George Washington, and Pericles. Their lives were full of action and courage, and I wanted to capture that same sense of adventure in my own life. As I grew older, great mentors and friends have shown me that the path to adventure and purpose can be found in a life of service to others.These friends and mentors have come from many different backgrounds. I’ve been blessed to work with volunteers who taught art to street children in Bolivia and Marines who hunted al Qaeda terrorists in Iraq. I’ve learned from nuns who fed the destitute in Mother Teresa’s homes for the dying in India, aid workers who healed orphaned children in Rwanda, and Navy SEALs who fought in Afghanistan. As warriors, as humanitarians, they’ve taught me that without courage, compassion falters, and without compassion, courage has no direction. They’ve shown me that it is within our power, indeed the world requires of us — every one of us — to be both good and strong.I hope the stories recounted in The Heart and the Fist will inspire you as these people have inspired me. They have given me hope and shown me the incredible possibilities that exist for each of us to live our one life well. –Eric Greitens

–This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

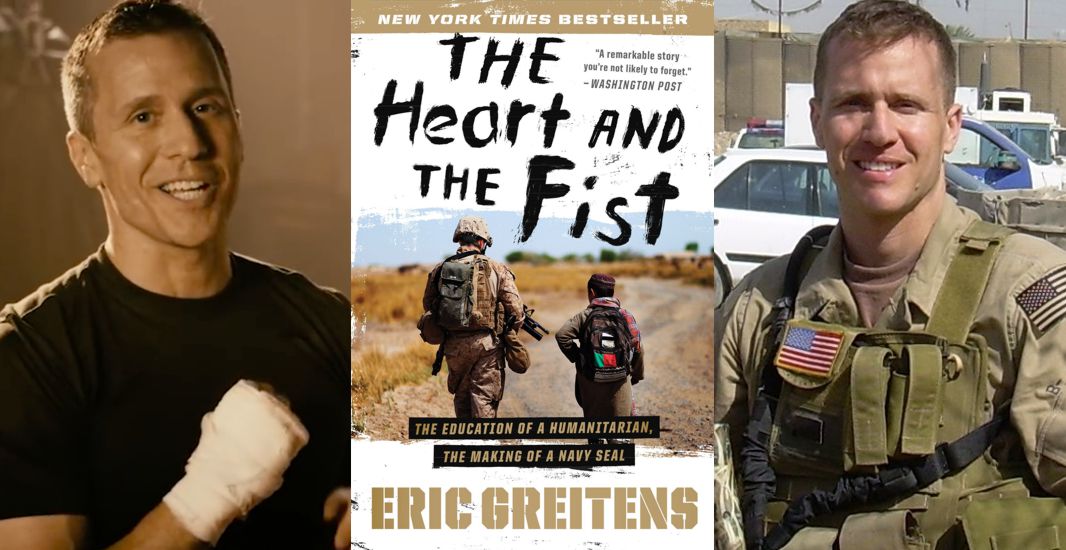

Eric Greitens was born and raised in Missouri. A Navy SEAL, Rhodes Scholar, boxing champion, and humanitarian leader, Eric earned his Ph.D. from Oxford University. He did research and documentary photography work with children and families in Rwanda, Albania, Mexico, India, Croatia, Bolivia, and Cambodia.

The founder of The Mission Continues and the author of the New York Times best-seller The Heart and the Fist, Eric was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people. Fortune magazine named him one of the 50 greatest leaders in the world. Eric lives in Missouri with his wife, Sheena and son, Joshua.

To learn more about Eric and his work, please visit www.ericgreitens.com.

From Publishers Weekly

This book, by Greitens, a senior fellow at the University of Missouri and founder of the Mission Continues charity, confronts the same dilemma as the American military, which strives to be a strong deterrent against the evils of the world while protecting the sick and powerless. The concept of a mighty warrior with a good heart is not an original one, but the humanitarian soldier epiphany comes to an idealistic Greitens after stints in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Gaza, and Calcutta where he sees unspeakable carnage and suffering without end. He takes the words of philosopher John Stuart Mill as his credo: “The person who has nothing for which he is willing to fight, nothing which is more important than his own personal safety, is a miserable creature.” The rigors of his Navy SEAL training are intensely depicted, as are his deployments in Kenya, Afghanistan, and Iraq, with Greitens slowly evolving into a balanced man with equal parts of compassion and warrior spirit. A glorious tale of humanity, resolve, and strength, Greitens’s book reminds us of how many things we take for granted in our well-ordered lives. (Apr.)

(c) Copyright PWxyz, LLC. All rights reserved. –This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

THE FIRST MORTAR round landed as the sun was rising.

Joel and I both had bottom bunks along the western wall of the barracks. As we swung our feet onto the floor, Joel said, “They better know, they wake my ass up like this, it’s gonna put me in a pretty uncharitable mood.” Mortars were common, and one explosion in the morning amounted to little more than an unpleasant alarm.

As we began to tug on our boots, another round exploded outside, but the dull whomp of its impact meant that it had landed dozens of yards away. The insurgent mortars were usually wild, inaccurate, one-time shots. Then another round landed—closer. The final round shook the walls of the barracks and the sounds of gunfire began to rip.

I have no memory of when the suicide truck bomb detonated. Lights went out. Dust and smoke filled the air. I found myself lying belly-down on the floor, legs crossed, hands over my ears with my mouth wide open. My SEAL instructors had taught me to take this position during incoming artillery fire. They learned it from men who passed down the knowledge from the Underwater Demolition Teams that had cleared the beaches at Normandy.

SEAL training . . . One sharp blast of the whistle and we’d drop to the mud with our hands over our ears, our feet crossed. Two whistles and we’d begin to crawl. Three whistles and we’d push to our feet and run. Whistle, drop, whistle, crawl, whistle, up and run; whistle, drop, whistle, crawl, whistle, up and run. By the end of training, the instructors were throwing smoke and flashbang grenades. Crawling through the mud, enveloped in an acrid haze—red smoke, purple smoke, orange smoke—we could just make out the boots and legs of the man in front of us, barbed wire inches above our heads . . .

In the barracks, I heard men coughing around me, the air thick with dust. Then the burning started. It felt as if someone had shoved an open-flame lighter inside my mouth, the flames scorching my throat, my lungs. My eyes burned and I squinted them shut, then fought to keep them open. The insurgents had packed chlorine into the truck bomb: a chemical attack. From a foot or two away I heard Staff Sergeant Big Sexy Francis, who often manned a .50-cal gun in our Humvees, yell, “You all right?”

Mike Marise answered him: “Yeah, I’m good!” Marise had been an F-18 fighter pilot in the Marine Corps who walked away from a comfortable cockpit to pick up a rifle and fight on the ground in Fallujah.

“Joel, you there?” I shouted. My throat was on fire, and though I knew that Joel was only two feet away, my burning eyes and blurred vision made it impossible to see him in the dust-filled room.

He coughed. “Yeah, I’m fine,” he said.

Then I heard Lieutenant Colonel Fisher shouting from the hallway. “You can make it out this way! Out this way!”

I grabbed Francis’s arm and pulled him to standing. We stumbled over gear and debris as shots were fired. My body low, my eyes burning, I felt my way over a fallen locker as we all tried to step toward safety. I later learned that Mike Marise had initially turned the wrong way and gone through one of the holes in the wall created by the bomb. He then stumbled into daylight and could have easily been shot. I stepped out of the east side of the building as gunfire ripped through the air and fell behind an earthen barrier, Lieutenant Colonel Fisher beside me.

On my hands and knees, I began hacking up chlorine gas and spraying spittle. My stomach spasmed in an effort to vomit, but nothing came. Fisher later said he saw puffs of smoke coming from my mouth and nostrils. A thin Iraqi in tan pants and a black shirt, his eyes blood red, was bent over in front of me, throwing up. Cords of yellow vomit dangled from his mouth.

I looked down and saw a dark red stain on my shirt and more blood on my pants. I shoved my right hand down my shirt and pressed at my chest, my stomach. I felt no pain, but I had been trained to know that a surge of adrenaline can sometimes mask the pain of an injury.

I patted myself again. Chest, armpits, crotch, thighs. No injuries. I put my fingers to the back of my neck, felt the back of my head, and then pulled my fingers away. They were sticky with sweat and blood, but I couldn’t find an injury.

It’s not my blood.

My breathing was shallow; every time I tried to inhale, my throat gagged and my lungs burned. But we had to join the fight. Mike Marise and I ran back into the building. One of our Iraqi comrades was standing in the bombed-out stairwell, firing his AK-47 as the sound of bullets ricocheted around the building.

Fisher and another Marine found Joel sitting on the floor in the chlorine cloud, trying to get his boots on. Shrapnel from the truck bomb had hit Joel in the head. He had said, “I’m fine,” and he had stayed conscious, but instead of standing up and moving, his brain had been telling him boots . . . boots . . . boots as he bled out the back of his head.

Fisher, Big Sexy, and I charged up the twisted bombed-out staircase to find higher ground. The truck bomb had blown off the entire western wall of the barracks, and as we raced up the staircase over massive chunks of concrete and debris, we were exposed to gunfire from the west. Iraqi soldiers from the barracks—this was their army, their barracks, and we were their visiting allies at this stage of the war—were letting bullets fly, but as I ran up the stairs, I couldn’t see any targets. At the top of the stairs, I paused to wait for a break in the gunfire, sucked in a pained, shallow breath, then ran onto the rooftop. A lone Iraqi soldier who had been on guard duty was already there, armed with an M60 and ripping bullets to the west. I ran to cover the northwest, and Francis ran out behind me to cover the southwest. As I ran, a burst of gunfire rang out, and I dove onto the rough brown concrete and crawled through a mess of empty plastic drink bottles, musty milk cartons, cigarette butts, dip cans, and spit bottles—trash left behind by Iraqi soldiers on guard duty.

As I reached the northern edge of the roof, I peered over the eight-een-inch ledge to check for targets and caught sight of a tall minaret on a mosque to the northeast. It was not uncommon for snipers to take positions inside minarets and shoot at Americans. It would have been a far shot for even the best sniper, but as I scanned the streets, I kept my head moving, just in case.

Women and children were scattered and running below us, but no one had a weapon. Far off to the north, I saw armed men running. I steadied my rifle and aimed. I took a slow breath, focused my sights, laid the pad of my finger on the trigger . . . no. Those were Iraqi police from our base.

I called to Francis, “You see anything? You have any targets?”

“Nothing.”

Nothing. The sun rose. We felt the heat of the day begin to sink into the roof. We waited. We watched. My breathing was still shallow, and I felt as if someone had tightened a belt around my lungs and was pulling hard to kill me. I glanced over the ledge of the roof again. Nothing. I assessed. We had plenty of bullets, and my med kit was intact. We had the high ground, good cover, and a clear view of every avenue of approach. We’d need some water eventually, but we could stay here for hours if necessary. Sitting there in a nasty pile of trash on the rooftop of a bombed-out Iraqi building in Fallujah, I thought to myself: Man, I’m lucky.

Travis Manion and two other Marines then ran up onto the roof. Travis was a recent graduate of the Naval Academy, where he’d been an outstanding wrestler. I came to know him while we patrolled the streets of Fallujah together. Travis was tough, yet he walked with a smile on his face. He was respected by his men and respected by the Iraqis. A pirated copy of a movie about the last stand of three hundred Spartan warriors had made its way to Fallujah, and Travis was drawn to the ideal of the Spartan citizen-warrior who sacrificed everything in defense of his community. He likened his mission to that of the warriors who left their families to defend their home.

I glanced at the minaret again. The sky was blue and clear. A beautiful day. The radio crackled with traffic informing us that a Quick Reaction Force of tanks was on its way. After the explosion and the gunfire and the rush of adrenaline, the day was quiet and getting hot. Tanks arrived, and a few Humvees rolled in for a casualty evacuation of the injured. Because we’d been in the blast, Francis and I were ordered to leave with the casevac for the hospital. I called over to Travis: “You got it?”

“Yeah, I got your back, sir.”

All the armored Humvees were full, and so a young Marine and I climbed into the back of a Humvee made for moving gear. The Humvee had an open bed. For armor, two big green steel plates had been welded to its sides. Lying flat on the bed of the Humvee, we had about as much cover as two kids in the back of a pickup truck during a water-gun fight. As we drove for the base, we’d be exposed to fire from windows and rooftops. We readied our rifles, prepared to shoot from our backs as the Humvee raced through Fallujah, bumping and bouncing over the uneven dirt roads.

When we’d made it out of the city, I asked the young Marine beside me if he was OK. “You know what, sir?” he said. “I think I’m ready to head home after this one.” Somehow that seemed hilarious to us and we both laughed our heads off, exhausted, relieved.

At Fallujah Surgical, I was treated among a motley crew of Americans and Iraqis, many half-dressed, bedraggled, bloody. I asked about Joel and was told that his head injury had been severe enough that they’d flown …