It is common knowledge that a suspect, armed with an edged weapon and within 21 feet of a police officer presents a deadly threat. Why? Because the “average” man can run that 21 feet in about one-point-five seconds; the same one-point-five seconds it will take that police officer to recognize danger, draw and point his weapon, and then pull the trigger. Even if the officer manages to get the shot off, and even if it hits the suspect; even if it instantly disables the suspect, the blade is going to be so close to the officer that the suspect’s momentum may continue forward with enough force for the edged weapon to end up injuring the officer anyway.

The information contained in the above paragraph has long been accepted in police and court circles. “If a man has a knife and is within twenty-one feet, he presents a deadly threat and the use of deadly force against him is justified.” Here is the question then: How far away does that suspect, armed with an edged weapon, have to be before he’s not a deadly threat? A gentleman named Magliato shot a “bad guy” who was armed with a baseball bat and standing thirty-two feet away. The courts convicted Magliato claiming that at a distance of thirty-two feet, the suspect with the baseball bat could not present deadly force against Magliato; perhaps they were wrong.

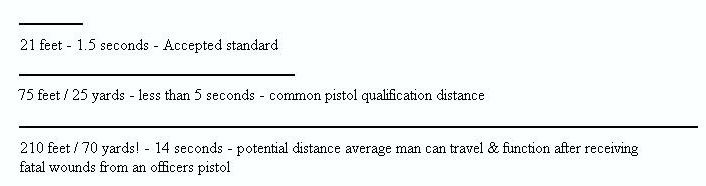

21 feet – 1.5 seconds – Accepted Standard

75 feet / 25 yards – less than 5 seconds – common pistol qualification distance

210 feet / 70 yards – 14 seconds – potential distance average man can travel and function after receiving fatal words from officers pistol

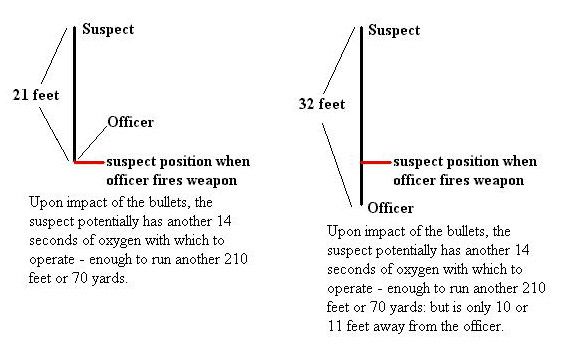

If it takes a man a mere one-point-five seconds to run across twenty-one feet, how long would it take to go thirty-two feet? The simple answer would be to add half, right? If thirty-two feet is about one-and-one-half times twenty-one, then one-and-one-half times the time of one-point-five seconds should be correct. Wrong. That one-point-five seconds for running twenty-one feet is from a dead stop. To assume that thirty-two feet would take fifty percent longer would be a mistake because you would have to assume that the bad guy started, stopped at twenty-one feet, restarted and then reached thirty-two feet. Reality is quite different. If you accepted that logic, the time would be about two-point-two-five seconds. In reality it would be less than two seconds.

Even if we worked with that two-point-two-five seconds as a realistic number for covering thirty-two feet, how many feet per second is that? It’s an average of fourteen-point-two feet per second. Now accepting that, let’s consider the cop with his gun holstered and the bad guy thirty-two feet away with an edged weapon or other form of lethal force. He starts running at the cop. The cop recognizes the danger, draws, brings the weapon on line and fires. The bullet hits the bad guy when the bad guy has traveled about twenty-two feet or is about ten feet away from the officer. In less about two-thirds of a second after the bullet impact to his body, the bad guy will get to the police officer and begin his attack.

Two-thirds of a second: Even if the officer fires two shots and gets good hits with both of them, the bad guy may have enough oxygen and adrenaline in his system to keep moving, in complete control of his motions, for another six to fourteen seconds! As mathematics just proved, the bad guy could run well over thirty-two feet in far less than six seconds, and we all know that the officer can’t run backwards even half as fast as the bad guy can run forwards.

Sure, someone reading this is saying, “That’s why we run in an arc so that as they lose control of their system, their momentum will carry them forward and we’ll no longer be there.” Ask yourself this: Have you tried running backwards, constantly moving in an arc, trying to keep a weapon tracking on someone who is attacking you with a knife or other deadly weapon for more than fifteen or twenty feet? Give it a shot some time. Have a fellow officer run at you hard for fifteen and a half seconds (did you forget the first one-point-five seconds?) while you try to run at an angle backwards. Do this in a soft area so that you don’t hurt yourself when you fall backwards as the “bad guy” plows over you.

With regard to this issue, there is more thinking and math to do. If you accept that the average man can run more than thirty feet in about two seconds, how far can he run in that fourteen seconds after your bullets have struck him and done serious damage to his vital organs; after he has begun to bleed out? At thirty feet per two seconds, that’s about two-hundred-ten feet: seventy yards! More than two thirds of a football field is how far you would have to run backwards in an arc to consider yourself safely away, and even then you’re assuming an average man with lethal injuries who has not consumed any substances that would affect his performance.

Obviously some disparity exists here. A man thirty-two feet away, holding a deadly weapon, didn’t present an immediate and deadly threat to Magliato, but a man seventy yards away can present a deadly threat to you, an armed and trained police officer? Think about it for just a moment and consider this: there is certainly no way that a man seventy yards away with a knife, bat or other contact weapon can immediately harm you. However, if that same man starts running at you with the obvious intent of doing you bodily harm, one would think it prudent not to wait for him to reach the twenty-one foot mark before firing your sidearm. It would probably be even more prudent to keep obstacles between yourself and the threat so that the time it takes him to close distance is even greater.

Finally, we can all foresee the juror who says, “How much damage can an injured man armed with a knife do against an uninjured police officer armed with a gun?” Well, you all know that bullets do not instantly stop anyone unless you achieve the more-than-rare central nervous system hit. As all officers are trained to shoot for “center mass” since it is the largest target and therefore presents the best chance of actually hitting the armed assailant, there is little chance that the rounds, if they hit the assailant, will pass through his body exactly on center to impact his spine and immediately stop his threatening actions. So, excepting that central-nervous-system, you know that the assailant can function as described above, for another six to fourteen seconds or until his system finally runs out of oxygen and adrenaline.

At contact distance, in a time span of six to fourteen seconds, what can you do as a police officer with a firearm? Shoot him several more times increasing the amount of tissue damage done and reducing the amount of time it will take him to “bleed out”. By the way, you have to do that while fending off whatever attack he presents. What can the assailant, armed with a knife, and within contact distance do to you in that same time span? Common sense suggests that he could stab you anywhere from twelve to twenty-eight times, everywhere he can reach, substituting slashes for stabs as he sees fit. That doesn’t sound like a good time. Further, no where in any cop’s job description does it say you have to fight an assailant with a knife since you are specifically equipped and trained to avoid getting into that situation.

So, you say to yourself, if there is no specified distance at which you can readily assume an armed assailant is too close and deadly force on your part is justified, how do you know when it’s okay to shoot? Just as with the use of deadly force against any threat, four factors must exist prior to your response with deadly force. 1) Opportunity: your assailant must have the opportunity to bring killing or crippling power to bear. This is the factor that is most affected by distance. A man with a knife can’t do you harm at fifty feet, but at contact distance he definitely can. How quickly he can close that distance and how quickly you can stop him has a direct affect on his opportunity to do you, or others, harm. 2) Ability: the assailant must have the ability to bring killing or crippling power to bear. Ability can exist in a number of forms such as weapons, overwhelming size, physical strength, force of numbers (in the case of more than one assailant) or special knowledge on either part. If the assailant has a gun or knife, that creates his ability. His size and/or strength can also create his ability to do you, or others, harm. If there is more than one assailant, together they stand a better chance of doing harm than when alone. Special knowledge is a two edged sword. You can have special knowledge of the assailant’s proven intent or skill; such as he’s a professional heavyweight boxer. That skill in heavyweight boxing is special knowledge that he possesses that makes him a greater threat. 3) Imminent jeopardy is the third factor and must exist prior to your deployment of deadly force. If the assailant does not present imminent jeopardy to you, or others, you cannot justify the use of deadly force. To some extent, “imminent” is controlled by distance. Again, that guy at fifty feet may not be presenting an imminent threat, but when he starts to move toward you, the threat he produces easily becomes imminent.

The fourth, and final, factor is preclusion. Any prudent person will normally make an attempt to escape or avoid the situation, which may lead to the use of deadly force. Police officers don’t have a requirement to retreat, and certainly conditions can exist wherein the police officer has no choice but to stand his ground. The duty to protect others may mandate that you face the threat without the option of running from it. The statement “preclusion is the fourth factor” truly means that avoiding the situation has been considered and is not a viable option. The officer must be able to articulate, along with all three other elements, why he didn’t, or couldn’t, avoid this deadly force confrontation. In the case of a man with a knife, bat, or other deadly contact weapon, once he (the bad guy) starts charging you (the police officer), his ability to close distance and deliver a killing or crippling injury is far greater than your ability to escape or stop his attack. If he is within the distance we typically train at with our handguns (twenty-five yards or seventy-five feet is usually the maximum distance), then preclusion is removed as soon as he begins his charge. All the mathematics above should have adequately demonstrated that he can close seventy-five feet in less than six seconds and that, even if you score good disabling shots while he closes, he may still have plenty of operational time remaining in which to do you potentially fatal harm. Therefore, it is maintained that, if he is within trained handgun distance, seventy-five feet or less and is armed with any type of killing or crippling contact weapon, imminent jeopardy exists and preclusion, as an option, has been removed. At that point, all four factors exist for your justified use of deadly force in defense of yourself or others under your protection.

To review: it’s takes one-point-five seconds or less for an armed bad guy to close twenty-one feet and do you bodily harm. It takes less than two-point-two-five seconds for that same bad guy to close thirty-two feet and do you bodily harm. After you’ve shot the bad guy, he has enough oxygen and adrenaline in his system to close another two-hundred-and-ten feet (seventy yards!) and do you bodily harm. The next time you are in an “Edged Weapons Defense” class, bear this in mind.

The next time you pull up on the scene of a violent domestic and that guy has a hammer in his hand in his front yard, bear this in mind. The next time you decide to park you cruiser within twenty feet of a vehicle on a traffic stop, and you officers on the street will all have to do exactly that, bear this in mind! You rarely know who the bad guy is, and you never know what the bad guy is bringing to the fight. As an instructor friend of mine is so fond of saying: “You always want to bring a gun to a gun fight. What do you want to bring to a knife fight?” Many of the people in the classes he teach respond with, “A knife.” He smiles a knowing smile and says, “No; a gun.”