This translation originally appeared in Vol. 29, No. 1 of the Hiroshima University of Economics Journal of Humanities, Social and Natural Sciences.

Translator’s Introduction

Over the course of the relatively short history of karate in the West, one of the most debated and discussed aspects of this martial art has been that of kata training. Practitioners have both solicited and put forth opinions on such things as whether or not practicing kata is an effective way to learn to defend oneself, how prominent a role kata practice should play in one’s karate training, the number of kata that one should “know,” and whether or not the practice of kata is even necessary.

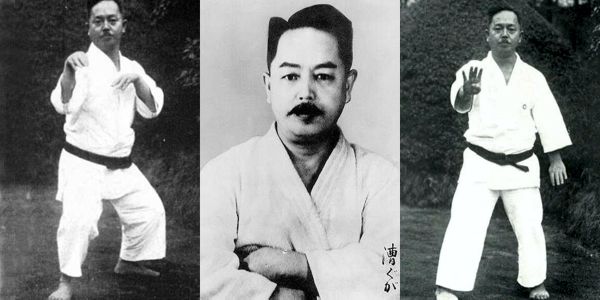

One voice that can speak with some authority with regard to this topic is that of Kenwa Mabuni, the founder of the Shito-ryu school of karate and one of four Okinawans typically given credit for introducing karate to the Japanese mainland (Iwao 187-211). Mabuni learned from such legendary figures as Anko Itosu, Kanryo Higashionna, Go Kenki, Seisho Aragaki and Chomo Hanashiro (McCarthy 1-37), and reportedly knew nearly every kata in existence in Okinawa (McCarthy 11; Iwai 207, 210) (1). Not only that, but venerated karate sensei (and Mabuni contemporary) Hiroshi Kinjo told McCarthy that, whenever someone – including the famed Gichin Funakoshi – wanted to learn, to have corrected, or to better understand the applications of, a kata, it was to Mabuni that the person went (McCarthy 25). Clearly, the Shito-ryu founder was an expert (if not the expert) when it came to kata.

In addition to his expertise with what some might term the “theoretical” side of karate (i.e., forms practice and analysis), Kenwa Mabuni apparently also had some experience with the more “practical” side of the art: McCarthy states that one of Mabuni’s leading students, Ryusho Sakagami, described his teacher as someone who had had his share of street encounters while working as a police officer. McCarthy also goes on to note that Mabuni’s son, Kenei, “said that his father often told him how his karate-do had helped him as a street cop” (McCarthy 24) (2). In a similar vein, Noble reports that Kenei wrote:

In his younger days many people would challenge my father to ‘kake-dameshi’ (challenge match or exchange of techniques)… He accepted these challenges… Each contestant would bring a second. There were no special dojo like there are today; we used to train and fight on open ground. There was no street lighting so after dark we used to fight the challenge matches by the light of lanterns. In this dim light the contestants fought, and then after a period the seconds would intervene and stop the fight… Such challenges were often made to my father… (Noble) (3)

Thus, Mabuni could hardly be considered a “paper tiger” who excelled only at kata: Given the accounts noted above, the Shito-ryu founder would seem to have also known the nature of “real fighting” and self-defense situations. Clearly, his thoughts on the role of kata in karate training are worthy of examination.

The Context of “Practice Kata Correctly”: Karate Kenkyu

Mabuni’s short essay being translated here, “Kata wa tadashiku renshu seyo” (“Practice Kata Correctly”), appeared in the book Karate kenkyu (“Karate Research”), which was first published in 1934, and then later republished in 2003. The book is a collection of essays and other writing by a variety of authors. In addition to “Practice Kata Correctly,” Mabuni also contributed his two-page “Kumite no kenkyu” (4) (“Research on Kumite”) to the publication. Some of the other titles found in Karate kenkyu include: Gichin Funakoshi’s “Seikan wo ronjite do-sei itchi ni yobu” (“Discussing the Concept of Calm Observation: Action and Stillness Together”) (5), Choki Motobu’s “Karate isseki-tan” (“An Evening of Talking About Karate”) (6), Kanken Toyama’s (7) “Chibana-shi no Kusanku” (“Chibana’s Kusanku”) and Hoan Kosugi’s “Karate-den” (“Karate Stories”) (8). Among the other pieces in the book are such varied titles as “The Fist and Virtue,” “The Effects of Karate-jutsu on Blood Pressure and Urine,” “Zen and Kendo,” “Foot and Hip Issues,” “A Girl Karate-ka” and “The Current State of the Karate World.” In total (and excluding the mention of the opening four pages of photos), the table of contents of the 135-page Karate kenkyu lists 36 essays and other items (9).

The editor of Karate kenkyu was a man named Genwa Nakasone. Though perhaps not very familiar to today’s practitioners, Nakasone was involved with various karate-related publications in an editing, writing and/or publishing capacity during his lifetime. The 1938 Karate-do taikan, for which he served as editor, was, according to McKenna, “out of all the early works on Karate-do published during the 1930s, one of the most comprehensive and important…” (McKenna 28). Kobo kempo karate-do nyumon, which Nakasone co-authored with Kenwa Mabuni, has been described (again, by McKenna) as, “… one of the most detailed texts on Karate-do ever written” (McKenna 28). On a somewhat different note, McCarthy states that Nakasone is remembered for organizing the so-called “Meeting of the Masters” in 1936 (McCarthy 30) (10).

It is interesting to note that, although Karate kenkyu has thus far been referred to here as a “book,” it would more accurately be described as the first issue of a journal or a magazine of sorts. In an editor’s postscript at the very end of the publication, Nakasone writes: “I am at last able to present the first issue of Karate kenkyu” (11). He then goes on to explain that, “At first, I wanted it to be a monthly publication, but upon looking into this in various ways, I came to see that it is still too soon for that…. For the time being, I’d like to make it a quarterly…” (Nakasone 135) Unfortunately, it would seem that no subsequent issues of Karate kenkyu were ever released, but the original intention to publish such issues regularly provides a more understandable context for the aims spelled out for the publication on one of its first pages:

- To be a mechanism for comprehensive research for the purpose of the development of our country’s karate-do, with all “styles” included

- To be a mechanism for technical research for those who train in karate-do, and, at the same time, to be a mechanism for their mental / spiritual cultivation

- To be a mechanism for cordial communication between karate-ka

- Karate kenkyu shall also carry materials regarding other budo, forms of exercise, etc., that ought to serve as both direct and indirect sources of reference for karate-ka

The page then ends with the statement that:

Karate-do is the budo which is best at cultivating the new Japanese bushido spirit. (Karate kenkyu 7) (12)

We can only wonder what further valuable and informative pieces of writing would have been left to karate historians and modern karate-ka had the plan to publish Karate kenkyu regularly been brought to fruition.

Translation of Mabuni’s “Practice Karate Correctly”

In karate, the most important thing is kata. Into the kata of karate are woven every manner of attack and defense technique. Therefore, kata must be practiced properly, with a good understanding of their bunkai meaning. There may be those who neglect the practice of kata, thinking that it is sufficient to just practice [pre-arranged] kumite (13) that has been created based on their understanding of the kata, but that will never lead to true advancement. The reason why is that the ways of thrusting and blocking – that is to say, the techniques of attack and defense – have innumerable variations. To create kumite containing all of the techniques in each and every one of their variations is impossible. If one sufficiently and regularly practices kata correctly, it will serve as a foundation for performing – when a crucial time comes – any of the innumerable variations.

However, even if you practice the kata of karate, if that is all that you do, if your [other] training is lacking, then you will not develop sufficient ability. If you do not [also] utilize various training methods to strengthen and quicken the functioning of your hands and feet, as well as to sufficiently study things like body-shifting and engagement distancing, you will be inadequately prepared when the need arises to call on your skills.

If practiced properly, two or three kata will suffice as “your” kata; all of the others can just be studied as sources of additional knowledge. Breadth, no matter how great, means little without depth. In other words, no matter how many kata you know, they will be useless to you if you don’t practice them enough. If you sufficiently study two or three kata as your own and strive to perform them correctly, when the need arises, that training will spontaneously take over and will be shown to be surprisingly effective. If your kata training is incorrect, you will develop bad habits which, no matter how much kumite and makiwara practice you do, will lead to unexpected failure when the time comes to utilize your skills. You should be heedful of this point.

Correctly practicing kata – having sufficiently comprehended their meaning – is the most important thing for a karate trainee. However, the karate-ka must by no means neglect kumite and makiwara practice, either. Accordingly, if one seriously trains – and studies – with the intent of approximately fifty percent kata and fifty percent other things, one will get satisfactory results.

Acknowledgments

The kind cooperation of the publishing company Yoju Shorin is gratefully noted. The translator would also like to express his thanks to his wife, Yasuko Okane, and to his colleague and friend, Izumi Tanaka, for their Japanese language assistance. In addition, he would like to acknowledge the role that Sensei John Hamilton and Senpai Michael Farrell have played in sparking his own fascination with kata. As always, any and all errors are solely the fault of the translator.

About the Translator

Mark Tankosich has dan rankings in both Sho-ha Shorin-ryu karate and Zen Nihon Kendo Renmei jodo. He reads, writes and speaks Japanese, and has lived in Japan for close to 15 years. Currently he and his wife reside in the city of Hiroshima, where he works as a university teacher.

Notes

- Mabuni’s son Kenzo stated that his father knew “over 90 different kata” (Fraguas 178). It is unclear if this figure includes those forms that Mabuni created himself.

- It is unclear exactly when or where the statements that McCarthy attributes to Kinjo, Sakagami and Kenei Mabuni were made, as McCarthy does not provide these specifics. Who Sakagami and Kenei Mabuni made their comments to is also uncertain, though it seems that it may have been to McCarthy himself.

- Unfortunately, Noble does not give his source for this quote.

- The title that appears on the piece itself, on page 28 of the book, is “Kumite no kenkyu,” while what is listed in the table of contents is “Kumite kenkyu,” sans the “no.” The meaning of these two titles is essentially the same. Variations in other titles in the publication can also be found.

- For an English translation of this, see McCarthy and McCarthy.

- For an English translation of this, see Swift’s “Karate Ichi-yu-Tan.” (Although this title which Swift suggests – “Karate ichi-yu-tan” – seems conceivable, it is this translator’s understanding that “Karate isseki-tan” is the correct reading for the Japanese characters making up the title of the essay.) As Swift notes, although the author of this piece is given as Motobu himself, “…the actual writer was a reporter…, presumably Nakasone Genwa,” who visited Motobu at his dojo in Tokyo (Swift 49).

- Kanken Toyama’s original surname was Oyodomari (Hokama 37). It is under this original name that “Chibana’s Kusanku” was written.

- “Karate-den” was originally published in the June, 1930 issue of a Japanese magazine before being reprinted in Karate kenkyu. For an English translation, see Swift’s “Hoan Kosugi.” Kosugi’s name may not be as familiar to the reader as the others mentioned here, but his contribution to the history of karate is a rather unique one. Apparently a famous painter in his time, Kosugi was the student and friend of Gichin Funakoshi who provided the illustrations for what is said to be the first book ever written about karate, Funakoshi’s Ryukyu kempo karate. He also designed the now well-known tiger drawing that has become the symbol of Shotokan karate. (Teramoto 15; Cook 65, 98)

- All comments made regarding the book Karate kenkyu are based on the 2003 reprinted edition. It is assumed, however, that this edition is essentially the same as the 1934 original.

- For an English translation of the minutes of this meeting, see McCarthy’s “The 1936 Meeting.” For a group photo of most of the masters who attended, see Kim (5).

- In the publication there are/were also other indications of Karate kenkyu being an inaugural issue.

- The translations of the “aims” and Nakasone’s words that are presented above them are this translator’s.

- “Pre-arranged” has been added here. Mabuni himself does not explicitly use this word, but it seems clear from the context that that is what he means. One would assume that his usages of “kumite” later in the essay also have this meaning as well.

Bibliography

Cook, Harry. Shotokan Karate: A Precise History. Norwich, Eng.: n.p., 2001.

Fraguas, Jose M. Karate Masters. Burbank: Unique Publications, 2001.

Hokama, Tetsuhiro. 100 Masters of Okinawan Karate. Trans. Charles (Joe) Swift. Okinawa: Okinawa Gojuryu Kenshi-kai Karate-do Kobudo Association & Karate Museum, 2005.

Iwai, Kohaku. Motobu Choki to ryukyu karate. Tokyo: Airyudo, 2000.

Kim, Richard. The Weaponless Warriors: An Informal History of Okinawan Karate. Santa Clarita, Calif.: Ohara, 1974.

Mabuni, Kenwa. “Kata wa tadashiku renshu seyo.” Karate kenkyu. Ed. Genwa Nakasone. Ginowan, Jap.: Yoju Shorin, 2003. 15.

McCarthy, Patrick. “The 1936 Meeting of Okinawan Karate Masters.” Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts Volume Two: Koryu Uchinadi. Comp. and trans. Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy. Boston: Tuttle, 1999. 57-69.

McCarthy, Patrick. “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: The Mabuni Kenwa Story.” Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts Volume Two: Koryu Uchinadi. Comp. and trans. Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy. Boston: Tuttle, 1999. 1-37.

McCarthy, Patrick, and Yuriko McCarthy, trans. “Seikan.” By Gichin Funakoshi. Funakoshi Gichin Tanpenshu. Comp. and trans. Patrick and Yuriko McCarthy. Virginia, Austral.: International Ryukyu Karate Research, 2002. 50-54.

McKenna, Mario. “The Life and Work of Karate Pioneer Nakasone Genwa.” Dragon Times Vol. 23: 27-29.

“Mokuhyo.” Karate kenkyu. Ed. Genwa Nakasone. Ginowan, Jap.: Yoju Shorin, 2003. 7.

Nakasone, Genwa. Editor’s Postscript. Karate kenkyu. Ed. Genwa Nakasone. Ginowan, Jap.: Yoju Shorin, 2003. 135.

Noble, Graham. “Master Funakoshi’s Karate: The History and Development of the Empty Hand Art. (Pt. 2)” Hawaii Karate Seinenkai Homepage. 28 Feb. 2006 http://seinenkai.com/

Swift, Joe, trans. “Karate Ichi-yu-Tan: A Night of Talking about Karate.” By Choki Motobu. Classical Fighting Arts Issue 2: 48-49.

Swift, Joe. “Hoan Kosugi: The Man Who Created the Tiger.” Dragon Times Vol. 19: 26.

Teramoto, John. Translator’s Introduction. Karate Jutsu: The Original Teachings of Master Funakoshi. By Gichin Funakoshi. Tokyo: Kodansha, 2001. 13-19.

By Kenwa Mabuni with Translation By Mark Tankosich, MA