In this essay I will share my observations of the Neihanchi kata of the Isshin Kempo and Isshinryu systems. I discuss Kiko and its relevance to Okinawan kata, and specifically to Neihanchi kata.

I do not speak Okinawan, Japanese or Chinese but I am very fluent in a certain kind of foreign language—KATA, specifically the dialect of the physical movement patterns of Okinawan Karate. I have been speaking this language for fifty years and teaching others how to become versed in its ways for over four-and-a-half decades.

When asked what drew me into the study of Okinawan karate; self-defense, fitness, competition, etc., my answer has always been straightforward—Kata. I did not know why the fighting forms of Asia compelled me such that I made their study my life’s career. In truth, I had no idea what Okinawan karate kata had to offer me in those early days. I only knew I just had to do it.

Over the past five decades my kata have undergone significant evolutions. But more important than my level of performance, my ability to mimic my teacher’s forms, my prowess in memorization, or the quantity of kata acquired, has been my insatiable desire to unearth the reasons for the exact composition of each of the engaging fighting choreographies of Isshinryu. Going beyond my own initial understanding is what matters most to me and defines real learning. For none of us can see beyond the limits of our own minds, so when we succeed at such, whenever we can expand our initial vision of a subject like martial kata, I have found that quality alone vitalizing, relativizing, and anchoring our martial skills in the present.

In this essay I will share my observations of the Neihanchi kata of the Isshin Kempo and Isshinryu systems. For those unfamiliar with the former style, Isshin Kempo was developed in 1970 by the East Coast karate expert, William Scott Russell. Isshin Kempo was an outgrowth of his study of Isshinryu. This system, which I have headed since Russell’s passing in 2000, can be considered Isshinryu’s Internal sister art. We utilize all the Isshinryu kata of Tatsuo Shimabuku but perform each under the light of Kiko principles inherent in their structure. The mainstream Isshinryu community is not aware of this level of technique. We consider this practice an art-within-an-art, and scarce in modern martial culture.

Before I discuss Kiko and its relevance to Okinawan kata, and specifically to Neihanchi kata, I‘d like to share my learning curve regarding karate kata, beginning with my introduction to the fighting dances of Okinawa in 1968, so you understand how I arrived at my current level of kata awareness.

In 1968, I was a skinny, seventeen year old, standing in a large, airy, high-ceilinged, pioneering martial studio, clad in a drafty pair of way too short, unbleached, twelve dollar, cotton pajamas. I had queued up alongside a group of other young kadets for our first, ‘This is Karate’ class.

Somewhere in the haze of that first year of hard physical training I was taught a Form; a precise, multi-move pattern consisting of staccato-like kicks, punches, blocks and stances. The exercise felt like a mythic karate ballet, the epitome of a savage combat art refined to its quintessential essence—killing. Killing expeditiously, killing artfully. At least that was the imaginative drama playing in my head as I swung my arms and legs like human katana against invisible threats.

A tiny % of people in the U.S. will ever seriously study the Neihanchi kata

I had no awareness of specific fighting styles or systems of martial arts back then. As far as I was concerned the karate I was practicing on this second floor, East Coast, pioneering suburban dojo was the karate the entire world was practicing, and kata, I was told, was a major part of my karate training. We didn’t question our sensei back then any more than we questioned our regular education teachers. As neophytes we didn’t know what to ask and even if we did, word got around quickly that directly querying your sensei, especially about your rank, could get you a punitive year’s extra extension of your current rank. We can thank the military cultures of both Japan and the U.S. for that kind of authoritarian attitude. So we trained like unquestioning, obedient suburban soldiers in an alluring and exotic art that we didn’t understand but couldn’t wait too learn. Our sensei pointed and we jumped through our martial hoops, assuming karate’s powers would be conveyed from sensei to seito by blind faith and sweat alone.

My earliest days of kata training were only to do without question, and do hard and long enough until I received my sensei’s nod of affirmation and was awarded another colored waist napkin to catch the heavy sweat rolling down my torso on my self-enduring quest to karate mastery.

Kata Bunkai

My second introduction to the many faces of kata work came through what our school somewhat mislabeled the shobu (duel/match). These were prearranged, situation-based, attack/defend/counter drills, what we now understand as prearranged kumite—an exchange, rehearsed mini-matches. One of us would attack and the other ritually slay our attacker in a highly controlled technical environment. We were told what to attack with and how to defend. In the mid-1960-70’s these drills formed the bread and butter of applied karate technique. Moves of a kata could be individually excised from the whole and drilled in a repetitive tori/uke relationship. However, while training from 1968-1975 not one of my three primary sensei ever offered concrete application of any kata from beginning to end. During this time period in American karate history it was uncommon to find dojos that systematically applied an entire kata to real-life encounters. The teachers often cited that solo Kata was simply part of ‘Traditional’ karate training. Period.

As the martial arts exploded on U.S. soil, so did the fascination to gain deeper understanding of the principles inherent in our training methods. Naturally, we wanted to know more about the history, philosophy and the techniques of our fighting systems. Dialogs sprouted up everywhere enhanced by emerging digital communication technologies as we sought a better foothold within our disciplines.

The biggest conundrum that existed for many young professional teachers in the 1970’s was caught in a single question made by an astute observer of a karate class. “If your kata is so important to karate why isn’t it more evident in your kumite?” Another way to phrase his question; ‘where does kata show itself relevant in real-life exchanges?’ For it wasn’t hard to see that the way we practiced kata and the way we fought was radically dissimilar.

This would begin my decades-long quest to answer this question and bridge the gap between two fundamental training modalities, kata and kumite.

One part of my puzzle got answered swiftly. Kumite in most dojos is considered ‘practice fighting.’ Because of the potential liabilities from injuries, karate kumite has not always been presented as real fighting but rather a staged, pseudo-acting version. The intent to injure is either diluted or completely absent. Kick/punch kumite was never designed as stage fighting, although many Western adoptees morphed their arts to be just that, an adult, role-play fight.

That still left the grand mystery. Why were the kata constructed precisely the way they were? What did the old world masters hope to convey in creating such dogmatic patterns? Does every kata hold the same value or does one kata offer something completely unique from another? Was technical redundancy common in karate kata on Okinawa? I felt these were important questions to answer if I was ever to understand the essence of karate Form.

I set about to interpret each and every kata in the Isshinryu syllabus, drawing insights from available literature, seminars with the experts, and years of trial and error practice. Like many first and second-generation sensei we didn’t see an initial, naturally built-in bias to our kata bunkai. Our interpretations were predominantly ballistic, i.e. strikes, with occasional takedowns. We were gleefully tackling all manner of ridiculous but fun scenarios; simultaneous kick attacks on our left and right, which the kata told us we could easily sweep away with confident, two-handed downward blocks; crescent-kicking rubber knives out of our partner’s hands. Executing bold, lunging block/punch moves (after adjusting our attacker’s distance so he’d be ripe for our well-placed blows). With hindsight, it was all a bit of oriental sleight of hand, appealing more to our runaway theatrical imaginations than a messy street fight. Looking back, we were just enough removed from a cagey, adrenalized brawl that I can see why Bruce Lee cringed when he observed Westerners trying to learn the trendy, karate line dance. Our bunkai was certainly athletic, but it was far afield from a sharp reality focus, and hence, in some ways, our kata-to-real-life link was deplorably unreal.

Kick-boxing emerged as a reality test of modern karate’s effectiveness

Somewhere in the late 70’s to mid-1980’s, kickboxing emerged as a primal desire to see if this karate ‘stuff’ really worked, and to make it work better, if not. That’s when kata bunkai began to mature and the gap between play and fight, to narrow. There were certainly schools that had a firm grip on their kata, but they were in the minority. It took the sobering, cold water sting of the televised defeats by the jujitsu men, organized by the Gracie family years later, to wake up and shake up the Traditional striking artists of the entire country to the brutality and realism of ‘anything goes’ matches. Karate’s fantasy kata playtime had come to a sobering crossroad. The message read clear to the Traditionalists—man up your arts or they will be left behind.

For many Westerners, Traditional karate held other allures besides pure fighting, which continues to commercially sustain these arts. Karate’s major trend in the mid-60’s-mid-80’s allowed it to develop strong roots in local communities. Add to this the intrigue and draw of karate’s one-punch-kill mystique that the movie media hyped, and those seeking an Asian philosophical sanctuary, a barefoot Zen retreat in a physical self-discipline, and you can see why many schools stay in business.

A small cadre of Western sensei saw the writing on the wall. Traditional kata would go obsolete if it didn’t get better grounded. If we couldn’t make a stronger case for why to perform kata other than the mantra, “it’s traditional,” if we couldn’t draw a stronger link to its value in a real fight then kata and the whole traditional ‘kit and caboodle’ would die out.

The Most Interesting Twist

It turns out we didn’t need to change our kata. Lo and behold! Our Kata stepped up to the plate when we actually viewed it under this stark light. We just needed to change the way we were looking at it. Kata’s worth had been there all along. We had been too immature, too naive, too limited in our thinking to see its vital lessons. Kata are and were every bit as lethal as we fantasized as young men. We just hadn’t figured out how to tap kata’s killer potency. And so the pendulum began to swing the other way. By simply changing our viewpoint our kata began to present us with pressure point lessons, joint-locks, grappling maneuvers, subtle energy cultivations, and a abundance of sophisticated anatomical knowledge for manipulating bodies in violent embrace.

Amidst this emerging and gratifying discovery, I had an even more astounding epiphany, a single event that made me realize that to this day in 2019, we still have not really understood the full face of Okinawan karate kata. That was the day Kiko principles emerged in my form. It didn’t happen all at once. It’s been a painstaking process, which I’ve been engaged in for the last twenty-five years.

Without Kiko principles, the full face of authentic karate kata will be generally misunderstood

I now believe that everything mainstream martial artists have been taught about their kata is likely half of its vital lessons. Many are in possession of a truncated art, as wise as one thinks they are, and as clever as one thinks their bunkai is.

I’ll let you decide how far you’ve come in your kata understanding as I unravel my mystery about the bunkai of Neihanchi kata.

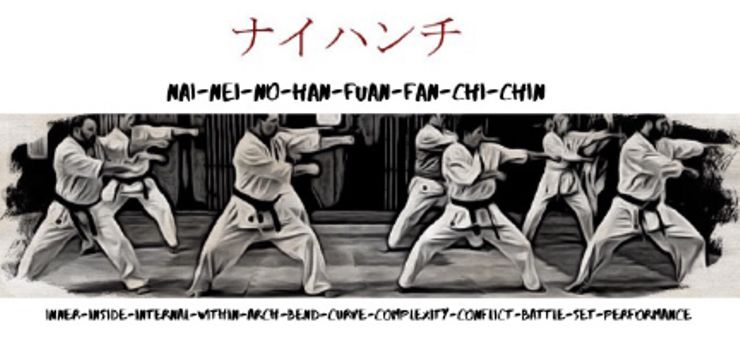

Many Names, Many Expressions

There are many variations of the Neihanchi kata. It can be found in the Shotokan, Shorin ryu, Shuri-Te, Wadoryu, Isshinryu, Shaolin Kempo and Kyokushin systems. No existing written historical evidence exists to clarify the origin of the form to date, so we may not ever know the original intent of the form. Some believe it is ballistic-based, grappling-based or a synthesis of the two. We can however, divine certain hierarchies of knowledge through the form’s technical composition, which in my opinion explains many of the reasons for its different variations.

I believe that the Neihanchi kata of Isshinryu came to western shores ‘mostly’ intact in terms of conveying its full spectrum of lessons. There were likely some omissions, additions, and/or modifications to the original form by T. Shimabuku and/or by his predecessors.

Let’s take a close look at Shimbuku’s sequencing of moves. Readers can have the same base to view my form breakdown by looking at Tatsuo Shimabuku’s Neihanchi kata video performance.

From the late 1960’s-1990’s I never came across any martial system that offered its practitioners a step-by-step methodology to interpret their kata.

To begin, why is Shimabuku’s Neihanchi kata, or any master’s Form, constructed precisely the way it is? Many do not realize that the Isshinryu Neihanchi kata is the only variation that initiates movement to the left. All other versions initiate to the right. Does this matter? We believe so, and Shimabuku may have understood the esoteric reason why.

What’s In A Name?

Do the various names for the form give us clues to its workings? From my vantage, very little, partly because it has been called by more than a half-dozen names with different characters and cryptic meanings: naifuanchi, naifanchi, neihanchi, naifanchin, naifunchin, and nohanchin.

The form is most widely known as nai (in my training—nei) hanchi. Both prefixes mean “inner, internal, inside or within”.

The Shuri-Te style Naifunchin is believed to have emerged from an earlier Chinese form called Naifanchin, no longer practiced in China. The kata was a primary conditioning form in the Shorin ryu lineage and believed linked to the Southern White Crane system. This probably doesn’t help anyone since most will likely never study White Crane. This kata may have been constructed for the same purpose as Chojun Miyagi’s modified, short version of Sanchin, to offer students a template upon which new techniques and applications could be birthed.

The general understanding is that the legs are being conditioned in the familiar Straddle Leg or Horse stance used throughout the form. The Horse stance (Chinese = mabu/horse step), not the formal, narrower Neihanchi kata stance of Isshinryu, is one of the kata’s main features.

The kata, also known as Horse Riding Form, may have prompted Funakoshi to rename it Tekki, for ‘Iron Horse’ or ‘Iron Horseman.’ Funakoshi’s renaming however, does not explain if his descriptor, Iron, revealed something of the technical nature of the form.

The widely accepted interpretation of the kata’s name as Internal Divided Conflict gives us little technical insight into the purpose of the form. We need finer historical clarification of what the Okinawans meant by ‘Internal’ in the context of their kata, and where and why the ‘divide’ occurs?

Other creative interpretations can be just as puzzling when you play with the form’s various names; ‘Nai/Nei’ = inner/inside, Han = bend/arch/curve, Fuan = crisis/complication, complexity, Chi = set or performance, Chin = battle/conflict. You could get ‘inner curve performance/battle,’ or ‘internal arched set,’ ‘Inside the battle curve,’ ‘Inner complexity conflict’, etc. Intriguing ideas, to say the least.

Funakoshi’s Tekki label was straightforward. Call the kata after its predominant stance, the Straddle Leg/Kiba dachi, and give it some panache with the descriptor Iron. But the whole situation is baffling when you realize that Isshinryu’s formal description of a Neihanchi kata stance is not a Horse stance as performed in Shotokan or other systems. An Isshinryu-style Neihanchi kata stance is a shoulder-wide, feet toed-in posture. A typical Horse stance is considerably wider with the feet straight. Various Neihanchi forms display stances that appear similar but I believe this kata uses a special variation of a Horse stance, which I will discuss later. In the Isshin Kempo system we perform the entire kata in one stance, the formal, Isshinryu, shoulder-wide Neihanchi.

My interpretation of the kata’s name yields; ‘An internally complex performance divided into multiple dimensions to deal with conflict.’

On one level it is obvious that the ‘divide’ is the two, near mirror image halves of the Form. The descriptor internal or inner suggests the divide is best grasped looking at the kata’s ‘inner’ dynamics. Unfortunately, most karate-ka don’t have a clue what this means.

Think of this kata as a fighting template divided into right-side/left-side functioning, and further divided as a north/south facing engagement. Let me explain; Neihanchi’s originator(s) probably understood that this form, in fact any kata, will have a slightly different technical expression when performing it right side/left side and facing north versus south. Few experts have caught onto this kata subtlety. And this difference is not about whether one is right or left-handed.

How would a sensei initially teach such a kata to a student? Which way should the student face if technique is influenced by directionality? Where should the student’s initial focus be? The early teachers of this knowledge may have had a conflict with how best to teach the kata given its subtleties of directionality and sidedness.

It’s safe to say that all authentic kata have been going through various stages of change; evolution, even of de-evolution. We can make a similar analogy to human aging. You might be called Billy as a child and William as an adult. Your childhood is certainly not the same as your adulthood, and no two people will ever perceive you identically. This is why we will always have different names, different expressions and different understanding for any kata. All the extant variations of Neihanchi kata are essentially offspring, all sired from the same source pattern and principles.

Fixed names, notions and techniques can limit students from delving deeper into their art. On the other hand, it can’t be ‘anything goes’ either. Unlimited comes with a different set of problems. So where do we start? If we interpret the kata as an internally complex set, then our first divide begins with how to best teach it in order to get its main points across. These main points must be clearly defined. We must determine if the Neihanchi kata is to be a ballistic form, a grappling form, a pressure point kata, a chi-kung practice, all the above, or something altogether different. Next, when we actually practice the Form, we can further divide the kata into two mirror sets with slightly different applications as a result of internal distinctions between the left and right sides of the body.

One of the biggest bones of contention amongst serious Western professional teachers of Okinawan karate is that many second-generation sensei learned their solo kata intact but few were taught a detailed methodology for deciphering them. Even more scarce, if not entirely absent, were any lessons imparted about a kata’s internal dynamics.

We do get a little help with the name when we look at the acupuncture term, ‘bend’ or ‘bends’, which refers to the body’s primary joints. In the arm this would be the wrist, elbow and shoulder joint. Gaining an inside position on an opponent to bend his joints to end a physical conflict is a good start for understanding an overarching purpose for Neihanchi kata bunkai.

The PUSH HANDS Connection

One of the two main branches of fighting art development that began in China is called Push-Hands (the other, bluntly put, glove up and fight). If Neihanchi kata had originally been designed as a basic, two-person, push-hand-styled training that explored various situations, including awareness of internal energy manipulation, we’d have something really engaging to teach our students. The British, Shaolin Kempo expert, Nathan Johnson, has done much in his published research to help us understand Okinawan kata’s link to Chinese push-hand drills. Push Hands exercises, more often erroneously attributed exclusively to the Soft arts like Tai Chi, allow two people to study the intermingling of energy fields to build sensitivity to degrees of energy exchanges during physical contact. Keep in mind that most karate sensei offer their students random kata applications and hope they can remember them should those specific circumstances arise.

As an aside, I remember being taught Seiuchin kata forty-five years ago in a Horse stance. It later dawned upon me that perhaps, the form should be taught in the Seiuchin or Shiko dachi stance after which it was named. Is there a point to naming the kata Seiuchin if there is no Seiuchin stance used in the entire form? Shimabuku took this form from the Gojuryu system where they use a Seiuchin stance. But Goju also uses 45 degree angles for the opening moves while Shimabuku uses a 90 degree angle. Why did Shimabuku change both the stance and the angle of performance?

In a personal interview years ago with the late Anthony Mirakian, head of Seibukan Gojuryu in the U.S., this master flatly commented about the difference with his quip, “Shimabuku didn’t know what he was doing.” My response to Mirakian’s assessment was that Shimabuku most likely did know what he was doing and demonstrated how the principles could be reworked in his version.

The point I stress is that Seisan kata utilizes Seisan stance. Sanchin emphasizes the Sanchin dachi. Shouldn’t it follow that Neihanchi kata ought to use the Neihanchi stance? Alright, Funakoshi changed the name to Tekki, literally, Iron Horse, which raised another interesting question. Are there Horse stances that are not iron? Can there also be a Water Horse, a Wood Horse, a Fire Horse, an Earth Horse? The Chinese Five Element Phases runs as a strong undercurrent in many Chinese soft styles and merits some consideration here. Is there a quality to an iron Horse that makes this stance unique? My research says, yes. Which brings us back to ask, what exactly is the Neihanchi stance? Is it a type of Horse stance?

What many do not realize, or seldom investigate, are the possible pressures in the feet and knees, which you can control when performing a Horse stance, that will effect your physical strength. First, a stance is not defined solely by the placement of one’s feet. A stance is a whole body configuration highlighted by differing foot placements. For example, in a Horse stance you can exert pressure to move your heels out, your heels in, your ball out, your ball in, the heels of one foot out with the ball of the other foot in, etc. And that is just the flexion of the feet. Consider the flexion of the knees, hips, neck and various breathing actions. These tensions will affect strength in the body’s musculature through a subtle signaling mechanism that some speculate takes place through the body’s cellular communications network, the fascia system, and is enhanced by greater hydration.

“Two people could be standing in an identical Horse posture and have markedly different outcomes.”

There are a lot of unanswered questions from the get go before we can start decoding Neihanchi’s bunkai. We must cover this ground first to anchor important fight concepts and establish a clear value between stance, movement and power. If you don’t know what your tools are how can you possibly use them correctly?

Salutation Or No Salutation?

A commentator on one of my training videos remarked that in the Koryu kata (old world) there is no bow. So what? In Isshinryu there is a bow. However, most Isshinyu karate sensei do not understand the chi-kung value of a proper rei to their opening kata bunkai. The rei for many is done solely as a perfunctory salute prior to initiating a form. In Shoshin Nagamine’s book, The Essence of Okinawan Karate Do this insightful master presents us with unique salutatory limb set-ups for different kata. Though this notable expert does not mention anything about chi, chi-kung or Kiko, it is obvious that to trigger maximum power for the opening kata bunkai it is essential one organizes the Strength Channels appropriately in the both the salutation and yoi or ready position.

Will we have a marked loss in bunkai if we do not bow in Neihanchi? No. But we won’t have any extra gain either.

This takes us to the opening of Neihanchi kata. After Shimabuku bows he lowers his two open hands left over right in front of his groin. He is not protecting his groin, unless he wants to do it at the expense of breaking his fingers. So why does he point his fingertips down? Why is his left hand placed over his right hand? Why not side-by-side, or right over left? Does it make a difference?

“The smallest moves can make a profound difference in strength”

There have been many creative bunkai attributed to this kata, many attempts to create applications for the entire sequence in the order of kata flow. But very few of these applications, in my opinion, offer an overarching purpose for the kata being designed exactly at is was. I’ve heard it said many times that Neihanchi’s leg-sweeping action will check kicks or unbalance an opponent’s legs, but that is just a fraction of the form. What is the point of the whole kata? Is there a common theme or technical thread being explored? Is it really the perfect form for fighting in a narrow alleyway, on a bridge, or with your back against a wall? Or is the form a general template where you get to fill in the missing bunkai blanks with whatever clever solutions you can conjure?

If, as it has been suggested, the Neihanchi kata was a central pillar in the Shorin-Te lineage, much like Sanchin was a foundational form for the Naha-Te lineage, shouldn’t we see a central theme running through the form’s bunkai?

I believe a basic flaw exists in the West’s understanding of most Okinawan kata bunkai. This flaw is a lack of tactical explanation for a kata, rather than the randomized responses most demonstrate. Many expert Sensei can show you the most ingenious of applications, hidden this and that – of course, many require the kata moves be partially or completely altered. I can’t tell you how many times I have witnessed a kata’s bunkai not matching the actual solo kata performance? This begs a big question. Was kata bunkai to be interpreted differently from its solo practice? Even if a kata was to be viewed as a resource, like a dictionary, what is the reason for its precise sequencing? For example, one effective bunkai for Neihanchi kata is to turn completely sideways to an attacker approaching from the front and strike his neck with a pressure point blow with the flat backside of your open hand. But we don’t see any turns in the solo kata. If this bunkai is so important why don’t we turn in the solo form? I’d like to hear from other experts what they think the value of the precise solo kata practice is if they interpret its applications differently.

Many instructors also feel this kind of loose interpretation is a liberty you’re allowed to take. I disagree with this learning method—in part. I say ‘in part’ because my own kata education has led me to both sides of the kata/bunkai debate. One side insists kata is a general blueprint, which you, as sensei or student, have the freedom to interpret any way you like, as long as you can make reasonable combat sense of it. In fact, in some schools you‘re taught a kata then told to figure it out on your own! That’s the blind leading the blind, in my opinion.

The other argument, coming from the bunkai orthodoxy, suggests that you or I cannot add anything significant, that a technique or concept has been so thoroughly fleshed out, you just need to perform it with its pre-given function in mind. (Sadly, most students are never taught this high end, pre-given function). I initially embraced the former method. It was the only one presented to me. But over the decades my thinking slowly shifted toward the later with great appreciation for Okinawan kata’s depth of composition.

Both points of view turn out to be valid. Both push you up the precipitous Mount Bunkai. Learning has many faces. The student’s mission is to keep broadening his/her understanding by any means available. One of the characteristics of truly skilled karate experts is their ability to adapt to any circumstance with their kata tools as a primer. This is something the novice, even intermediate level students cannot do. Adapting to a changing violent terrain with free-flowing effective responses takes the average person five years minimum to be able to insert strikes and locks effortlessly in an open style, anything-goes encounter.

Kata has been greatly undervalued in Western society. This is due to a general misperception of how to apply it correctly. First, one must understand what a kata is. All great kata are multi-dimensional treatises on the nature of martial technique. They outline the proper use of the physical body as a series of fluid tools. They engage the mind/body complex to develop effective tactics. They organize and integrate the biological and psychological systems for optimal functioning, and they reveal an internal Subtle Energy template, the form of no form, to activate the highest known principles of energy transfers.

I believe that Neihanchi kata, at its best, presents us with a tactical principle that if properly understood and consistently practiced, will narrow an opponent’s options of response, making it easier for you to succeed in a real exchange, because you will have less chance of a fumble when drawing from a small, precise pool of techniques rather than the mental burden of choosing from an unlimited technical inventory. Also, by this kata’s pre-selection of actions, your opponent’s choices of reaction are also narrowed, giving you a greater chance of success. So, the historical rationale of this kata as a superior method for fighting on a bridge, in a narrow alleyway, or with your back against the wall may be a Western misunderstanding of a deeper intent. I’d like to suggest a reinterpretation of Neihanchi’s purpose that offers us a way to ‘narrow’ our opponent’s options, putting his back against a wall, so to speak, as far as his responses are concerned.

Neihanchi’s Tactical Agenda

If you are applying Neihanchi using random bunkai, you will most likely fail in a free-style exchange, unless you are a professional, who can move fluidly with a wide variety of techniques and principles. This immediately rules out 95% of the Traditional karate community, as most practitioners will have less than two years experience.

Isshin Kempo Neihanchi wants you to engage in one of two, straightforward defensive strategies. Attempt a cross arm grab of one of you opponent’s arms or let your opponent attempt a cross arm grab of one of your arms. The kata’s actions then initiate.

This kata bunkai addresses and explores the compromise of being grabbed with a cross-hand grip, meaning, either your right is grabbed by his right, or your left by his left, or both are gripped and held crossed in front of you.

This is why the kata begins with your open hands in front of the torso pointing down. They have been pulled down and crossed. The kata begins with you being placed in the fully compromised position—the worst-case scenario. We present Neihanchi kata as an internal grappling form that offers a simple solution to the problem by using one of three locks, easily manageable, easily applied. The tactical agenda of this form is to lure your opponent into a narrow fight-response corridor, offer him a bridge to only a few possibilities. If he takes the bait, as you will see he has by gripping you in this manner, you’ve got his back up against a wall for ending the fight.

I am not suggesting this is the ultimate Neihanchi kata interpretation but this bunkai is near identical to Tatsuo Shimabuku’s actual performance and makes the Form far easier to remember.

So, we start with our hands compromised and crossed in front of us. What next?

I have to bring up something of a technical mystery in Shimabuku’s presentation. You will most likely miss this dimension unless you’ve been doing and questioning your kata for a long time. Time alone however, will not guarantee this training dimension will loom up. Shimabuku’s kata actions reveal Kiko principles, a layer of technique not commonly, or openly, discussed by contemporary Okinawan masters. To understand why the salutatory left hand is placed over the right is to understand why the optimal stepping is on a perpendicular angle to the left, as the kata suggests, with the first crossover step. Of course, you can do anything you want in a gross sense, but you will not be doing what we think the kata is asking us to learn based upon its precise patterning. So what is it about Kiko principles that have us adhere to a strict pattern of movement?

To Ki Or Not To Ki?

I must digress again to explain another aspect of kata to give you a foundation to the above question. In my opinion, kata has been broadly disintegrating since the Industrial Revolution in the modern world. It was degrading in Okinawa in the late 1800’s and its been degrading in Western cultures since its exportation outside of Asia. The downgrade began with the commercialization of the martial arts. This downgrade has occurred on two levels; Technical nuances have been gradually disappearing from kata to simplify karate for the general public (even more so today as the karate art is over-populated with children). Funakoshi faced a similar issue when introducing karate to the Japanese public in the early 1900’s. Second, Kata’s inner nature, its Kiko component, was not passed along. To put it another way, the manual that fully explained how and why kata’s external movements and its Kiko (internal movements) worked synergistically was not included. Some suggest that Kata’s internal nature was purposefully held back from Westerners as part of a closed-door policy to keep the art culturally pure. I would say this is partially true. The issue is more complicated. I believe that Kiko wasn’t even disseminated by, or made known to, the majority of Asian martial teachers either. This leaves us with a mostly external art and therefore players with middle-of-the-road kata interpretations. These karate-ka are not mediocre by their desire to learn or master technique or by their athleticism, commitment or bunkai intensity, but rather unexceptional by virtue of their lack of possession of the full kata formula. I was one of these successful but mediocre kata professors for twenty-five years. I was highly effective by civil-defense standards, even exceptional by the lay public, but run-of-the-mill by kata’s potential standards. Two mainstream karate-ka engaged in bunkai exploration will only see to the limit of their own minds what the moves of Neihanchi kata might fully represent. If you don’t understand martial Kiko your bunkai will be limited. This is how we get such variety in performance amongst styles and erroneous statements that one should be able to perform a kata in the mirror version as well. This is more often a direct violation of Kiko principles if you think the moves should be done exactly the same. We can prove in many cases this is mostly incorrect.

What Are Kiko Principles?

Kiko literally means Spirit Breath. The term is not be confused with the Japanese word Keiko which means, practice. The Kiko I am referring to is an old world Okinawan martial term for chi-kung, in our case martial chi-kung. Kiko is the art of manipulating subtle human energies to effect noteworthy strength changes in both yourself and/or your opponent/partner. In other words, triggering Kiko principles in your kata bunkai can make you markedly stronger and your partner significantly weaker. From my camp alone, we have over twenty-five years of research conducting thousands of tests with students of all ages and from multiple styles demonstrating these principles with repeated successes. Even more so ‘says,’ i.e. suggests, the actual patterns of the primary kata of Okinawa.

Kiko is different from simply ‘being strong’ or gains from bio-mechanically-induced strength training. Strength is not a constant variable but can wildly fluctuate with the flow of Ki into the muscles, which you can control. Your bicep is only as strong as the energy you can bring into and discharge from it. If the nerves to the bicep are severed the muscle cannot contract. Likewise, without Kiko principles activated, I might completely fail to break out of a two-handed grip. With Kiko properly applied I might escape effortlessly. This observation alone has made the subject worth investigating.

Leverage Is Not The Only Key. Sometimes ‘Ki’ Is Key!

There are many biomechanical leveraging and timing tricks that can give a karate-ka an advantage in applying or escaping from grips and locks. Kiko is an enhancement, not a replacement, for those tricks and basic skills. Kiko represents a finer layer of technical study.

So here you are with your hands compromised and the first movement the kata offers is stepping left with your right foot over your left foot. You do not step into a reverse cat stance. You do not arc your foot wide in front of your left foot to avoid it, nor lift it high. You step right over the arch of your left foot and then move your left foot by lifting and flipping it up to your knee height passing your ankle in front of your right leg and placing it down into a Neihanchi stance.

Is Neihanchi a toed-in, high (narrow) hybrid Horse stance? After a quick perusal on the Internet, it’s clear to see the disagreement as to what defines this stance specifically as Neihanchi. The manner in which you go into a stance is as important as the static posture itself. How do you toe-in? Do you turn your toes inward, or move your heels outward? These are two very different Kiko actions with distinctly different outcomes. The correct method is to turn your heels outward.

Is Neihanchi a Horse stance as other styles demonstrate? If so, Neihanchi may be a distinctly different kind of Horse stance from a ‘common’ Horse stance. I define a typical Horse stance as one-and-a-half times shoulder width with feet straight, knees bent and pressing outward. I define a Neihanchi-style Horse stance as one-and-a-quarter shoulder width apart with the feet straight but with the toes pulling inward.

So why are we moving to the left versus the right? What possible situation might occur in which we would have to step this way? Why not step back or forward? Does it matter which direction we initiate our footwork?

Direction Matters

My observation is that most Okinawan kata move in the direction best supported by Kiko principles, specifically when considering the offensive actions of an opponent in close proximity. Think of it as moving with an invisible tide. In this case, we want to move in sync with an intrinsic, electro-magnetic field flow generated by, and coming off, each person. In Seisan kata of Isshinryu that direction initiates with a left foot forward; in Sanchin kata, right foot forward. In Seiuchin kata, it is right foot forward ‘if’ you step diagonally as done in Gojuryu. A clever challenge to this theory might be to point out that in Shotokan’s Tekki Shodan, you move to the right first. But this crossover step is done in a wider stance, an Iron Horse stance, not the narrower Neihanchi dachi. The narrower toed-in Neihanchi and Iron Horse stances are synonymous only by adherence to Kiko principles not by identical posturing. From my personal experience there is a proportional width that defines the Neihanchi/Iron Horse — a stance formula where the leg width can vary but the principles remains the same with nuanced tensions applied. This is why you can have a narrow, toed-in stance and an Iron Horses stance, a shoulder and a quarter width with toes in, and get the same results.

Consistent with both the Isshinryu, Shotokan, and other variants, there is also no similar first step across when repeating the form on the opposite side, i.e. starting the second half of the kata. The Shotokan Tekki also avails itself of Kiko principles, the primary one being that sidedness is energetically different when executing martial technique right versus left. This is why doing an exact mirror image of a kata will often be fundamentally wrong. And this would not be apparent unless specific tests were given to show your decline in strength when you violate Kiko principles. But again, we reach another tricky overpass. Playing my own devil’s advocate, I could point out that there are many instances where a kata’s movement patterns are repeated on the opposite side or in the opposite direction. So what gives?

Our Bunkai Waters Are Getting Murkier

I believe most students and their teachers will never find the definitive answer for the left-moving direction of the Isshinryu Neihanchi kata unless they understand Kiko principles. Body energy flows differently through our left and right sides. The meridians may be bilaterally located but their individual conductivity varies greatly. Energy flows broadly out the right side of the human body and in through the left side. By initiating our step to the left we pull energy from the opponent’s right side into us. Think of a magnet (you) drawing iron filings (opponent), only the whole process is happening on an unconscious and invisible plane. In addition, this pull will only take place effectively if you move horizontally and stay relaxed. If you step to the left forward diagonal you will markedly increase an opponent’s grip strength and may not be able to break the hold at all. And if you step too far to the left horizontally, the draw may also not work.

If you think Kiko is overkill on detail, consider how long it takes the average person just to master a single roundhouse kick.

The element of surprise will always work in favor of the applicator with or without awareness of Kiko principles and should not be used as evidence of the lack of necessity for this high-end practice.

Also, working in our favor is the leveraging aid of putting the opponent’s arms out of alignment by making him cross his own centerline when we step to the left while twisting his right wrist. This reduces any further threat from his right arm. We want the opponent to hold long enough for us to reverse the grip(s) on him.

I’d like to make a case that this bunkai in Neihanchi kata teaches the proper use of an overhand grip to tie up our partner. You must rotate your palm up first before you grab.

Our goal then is to reverse the situation of our compromised hands, and instead lock up both our opponent’s arms, narrowing his responses, rendering him incapable of striking back.

There are so many facets that need to be fleshed out to fully understand the workings of internal energies in kata that it often takes one being an intelligent and advanced karate practitioner to absorb them.

Now I would like to discuss an odd phenomenon that exists in many schools. It is one of the reasons why you might never see Kiko principles at play. Let’s call it the ‘dojo drift’. Rather than dojo participants getting a clearer view of their karate technique, a skewed reality forms as a result of a group-conscious collaboration to make the technique work in a less than real way. It can go like this; I know my partner is going to put me in an arm bar. He appears to be doing to it correctly, so I am going to subtly comply with his move, since it hurts anyway. An entire school can be lulled into this group technical self-hypnosis. One extreme example was of a Japanese master who claimed to be able to toss most of his class about without touching them. Students approaching him would all go flying willy-nilly through the air as if hitting a super magnetic field. But he couldn’t do it to anyone outside of his dojo! This is similar to the way a mentalist works. They pick the most suggestible subjects with a high likelihood of success. The same phenomenon can easily happen in a karate dojo. Eventually, the senior line consists of the most susceptible followers.

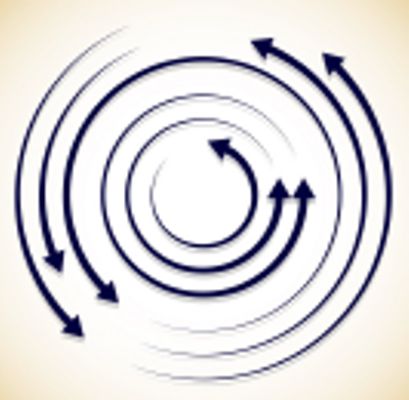

Spinning The Rings

The opening footwork in Neihanchi kata reveals a Kiko principle we call Spinning the Rings. Electro-magnetism possesses two general qualities; electrons move linearly while the magnetic field rotates. We effect the rotation of the magnetic fields of the body when we cross any limbs. Imagine that your left leg has an invisible, suspended ring around your ankle, which we ‘friction-kick’ when we step with our right foot across it. When a right foot steps frontally across a left foot it causes the left leg’s ring (magnetic field) to rotate counter-clockwise. A counter-clockwise action triggers energy to rise up or dilate the Yin meridians of the leg, which, in turn, charges specific muscle groups. Conversely, the ring on the right leg, by stepping behind the left, is spun clockwise, a yang, downward energy action. If we take a mental step back, we can see that the leg rings have been spun to draw energy in the left leg and out the right. In this case, we are enhancing the flow by increasing it with the crossover step. This explains why starting the Neihanchi kata to the right cannot be done in an Isshinryu Neihanchi stance, but must be executed in a Iron Horse (a slightly narrower full Horse) with toes pulling inward, otherwise the opposite result would occur with the crossover step leading to a weaker technique. To remedy this issue requires one step wider and, in addition, create an energy backdraft by lifting up the right knee before placing it down.

Why Is The First Hand Motion Of Neihanchi Kata An Open Palm Moving To The Left?

While some dojos execute the first arm motion with a left open hand palm facing upward, others use a palm sideways action. Some shuto/chop and finish by turning the palm up. In accordance with Kiko principles, a left open hand, palm up, creates a strong energy draw if used to break a grip or deflect a strike. In our bunkai we want to circle our left hand over the top of an opponent’s left hand grip to maximize our energy draw to control and lock his arm. The hook/block in Seisan kata works in a similar manner. This circle-the-grip counter-action is a good example of a nuanced movement. We cannot deduce that Shimabuku, in his videotaped solo performances, circles his left arm over an imaginary left arm of an opponent. But we believe this to be a viable action (moves like this are often implied in kata, particularly when you see the retraction of an arm into the side chamber at the waist). This is followed by clamping down on the opponent’s left arm, then twisting it counter-clockwise into a palms-up chamber at our left side.

A chambering hand or hiki-te often shows how a trapped arm is to be held. Our action accomplishes three levels of control. One, we take energy away from our partner. Two, we render his left arm less effective for drawing back to his side, and three, we position his left arm for an arm bar with our right forearm.

“Wait a minute! You say. “If our left arm is an energy draw, isn’t his a draw as well? Won’t he be drawing from us, canceling out our benefits?” The answer is that as soon as we cross his left arm over his centerline to his right, his drawing arm becomes a sending arm and his strength decreases considerably.

The internal art of Kiko is every bit as rich and complex as the external art of overt, biomechanical karate waza. Just as there are principles of biomechanical leveraging to maximize strength, there are principles of bioenergetic leveraging awaiting the curious.

Can’t hear it, can’t see it, can’t talk about it

I Don’t Believe It!

Someone once asked me if I was looking too deeply into the kata. Absolutely! That’s what studying an art is all about. I’ve got the time and the energy, and the outcome of our on-going research has been too remarkable to deny. I’m not forcing anyone to believe me. You can stick with what you know.

We’ve tried to disprove Ki from every possible angle and we’ve failed too date. Our observation is that there is a biological phenomenon taking place in physical movement patterns and actions amongst two people that reveal demonstrable, sometimes radical, affects upon physical strength that cannot be adequately explained by Western-known physiological processes. This essay is about sharing what our school has observed, and for those interested, testing our hypothesis on your own. We also invite any martial artists to witness these principles for themselves and describe in their own terms what is happening.

My second assertion about Kiko was formed around the uncanny coincidence of Okinawan kata’s technical nuances perfectly matching its movement patterns to Kiko principles. I did not invent Kiko, Ki flow, Internal martial arts or the phenomenon associated with the extraordinary strength elicited when either making these adjustments in the kata or performing an unadulterated kata. I did not invent Okinawan karate or its kata. Okinawan karate strongly affirms kinesthetic artifacts of valuable, applicable, esoteric information encoded in their patterns. This is why the most essential kata were taught with utmost attention to detail. Devilish power lies in these details.

Our testing group has consisted of highly intelligent and educated individuals from academics, engineering, acupuncture, athletics, law enforcement, biophysics, science, as well as high dan-ranked members of Okinawan karate, Tai Chi, Aikido, Isshinryu, and the Buddhist Wu Shin Tao community. They’ve all witnessed for themselves the affects of KIKO principles.

Recently, I spoke with a man who has spent sixty-five of his eighty years studying a broad span of martial disciplines from Isshinryu to Gojuryu, to Tai Chi and the Liu He Ba Fa (Water Boxing). His observation was blunt. ‘No one wants to think deeply about the karate arts anymore. This is why these arts are receding. Karate is an art for intelligent people.’ Perhaps this is a good place to start a dialog. Are we becoming a superficial, over-reactionary, skim-the-surface culture? Did we get the kata right? Why is there so much resistance to rethinking the karate arts and their beloved kata?

To continue with the bunkai, the next sequence of Neihanchi kata reveals why variations may exist in other styles in the grappling controls we want to place on an opponent.

In the next move we lift our left leg, flipping it in front of our left knee—the infamous Neihanchi leg lift. In my early exploration and breakdown of this kata’s bunkai I could not justify the left leg flipping in front of the supporting leg. We saw instead evidence that lifting the leg inside the supporting leg was better aligned with KIKO principles, making for a stronger hook, block and arm grip.

Whether a left leg lifts inside or in front of the supporting leg both will yield different affects depending upon the height of the lift. The knee-height lift in Shimabuku’s form triggers specific strength channels in the arms.

Our initial focus on the inside lift versus Shimabuku’s outside lift wasn’t to discredit or to disprove Shimabuku’s way of performing the kata. We were simply entering into a complex field without clear sense of the mechanics of energy bunkai at that time and needed to reverse engineer our applications by understanding where inordinate strengths in the movements were evident.

The Neihanchi leg sweep, name ashi (returning wave), creates an electro-magnetic disruption to the others energy field resulting in their loss of physical strength.

Let me backtrack. In the Isshin Kempo system we have excellent, multi-tiered, topical bunkai for all the moves of Neihanchi kata, but as my Kiko knowledge broadened it became obvious that our surface bunkai was not always in sync with Kiko principles. This caused us to look deeper at what the potential bunkai in alignment with Kiko principles might be. One interesting example was discovered while researching the leg lift. The sweeping leg action is called Nami Ashi or returning wave. This curious interpretation gave us a critical hint. Could it be possible that the leg lift was returning an energy wave by brushing the other’s energy field a certain way? This turned out to be true and is both a fascinating phenomenon and impressive internal technique when done correctly.

Kiko’s influence in the kata was a slowly unfolding revelation and has proven to be highly valuable metric for understanding the precise configuration of any master’s kata. Remember, I have previously stated that much of the bunkai taught today often does not precisely follow a kata’s composition, nor does it have an overarching or connected purpose to the overall form, and even if it does follow the pattern closely, the individual bunkai often reflects a series of unrelated, random technique.

The next set of moves executes a right leg lift and what looks like a right backfist-style low block to the right side of your body followed by a palms-up spear across the torso.

The right leg sweep (the returning wave) creates a greater muscular contraction in your right arm for pulling your opponent’s arm down to your right side. This motion is followed by a spear.

Are you really going to spear someone across your body, and without moving your hips as Shimabuku’s kata suggests? I doubt it. There’s too much potential damage to your hand even if it were targeted at a throat. In my opinion, the likelihood that this technique is a viable fingertip spear hovers somewhere near zero. On the other hand, the likelihood that a ‘spear-like’ arm action is part of a grappling lock sequence is very high. Remember, we are looking to explain why a kata is done exactly as it is configured. If we add a hip motion to make the spear stronger we are altering the kata. If that was the intended move in the creation of the form we would see the hip torque fully emphasized? I sought to answer whether there was something else intended.

There is a variation of Shimabuku’s form found in Choki Motobu’s Shuri-Te that uses a solar plexus height fist strike (palm down) across the chest instead of the palms up spear. This action fits with our theory that the kata is offering a grappling nuance when applying an arm bar. An arm bar initiated at different points of positioning (height of opponent’s elbow relative to your torso) requires that you implement specific arm positions to maximize the hyperextension of the other’s elbow.

The Three Applications

If you grab your opponent’s wrist and twist it, and he bends nearly in half, or if he is shorter than you where his elbow hovers at the height of your abdomen, then Shimabuku’s, tanden-height, palms-up spearing action fits neatly across his elbow to apply the arm bar. If however, the opponent’s elbow is higher than your waistline because he is taller, or can’t be easily bent, a downward facing fist across his elbow will better secure the lock. If the opponent’s elbow is higher yet, perhaps, as a reaction to avoid your lock, or he pulls it back in anticipation of your lock, it will be necessary to slip your free hand under his elbow and roll it forward, moving instead directly into a shoulder lock. In the first two applications, we secure an arm bar as a set up for a roll into a shoulder lock.

These ‘hidden’ arm bar controls are rarely discussed technical levels. With Kiko principles we consider zones of control, proximities where the arm bar manipulation is enhanced. For example, the direction your palm faces with your free hand while gripping the other’s wrist is critical in manipulating the other’s arm energy. When you grab someone’s wrist you could hold it still, pull it toward you, back toward their shoulder, or push it away from you. All these gross and subtle actions reveal dynamic shifts in strength when applying an arm bar.

This is also part of the kata where I must raise the strong possibility of lost nuance. For I can pull an arm bar off in several ways and each method has been demonstrated by at least one of Neihanchi’s existing variants. Shimabuku’s palms up spear works well if the lock is applied to an opponent’s arm held around waist height. Motobu’s, Shuri-Te, chest-height fist works well if the lock is applied to the opponent’s arm when the elbow rests at solar plexus height. The shoulder lock is preferred when the opponent’s elbow is too high to bar.

Keep On Tekking!

The old Okinawan karate proverb, ‘Dig a small hole, Dig deep!’ hints at the treasures awaiting anyone’s effort to plow deep into their kata—more mystery as well. In this essay, I wanted to share with you some of the dirt and diamonds I’ve discovered in a lifetime of martial study. Perhaps it will pry your mind open just a bit more about Neihanchi kata and its exciting potential. Happy Digging!

The Other Way of Sanchin Kata