Totally Tae Kwon Do magazine recently spoke to Master Willie Lim, a pioneer of the art in New Zealand and a revolutionary in the area of ‘hidden’ pattern applications or kata bunkai, on his opinions on the state of Taekwon-do today and what he thought of General Choi.

The term ‘legend’ is an often overused one. But in Taekwon-do circles, it’s commonly used to describe the pioneers of the art. So to describe Master Willie Lim as anything but legendary, is not only a bit disrespectful, but just plain wrong.

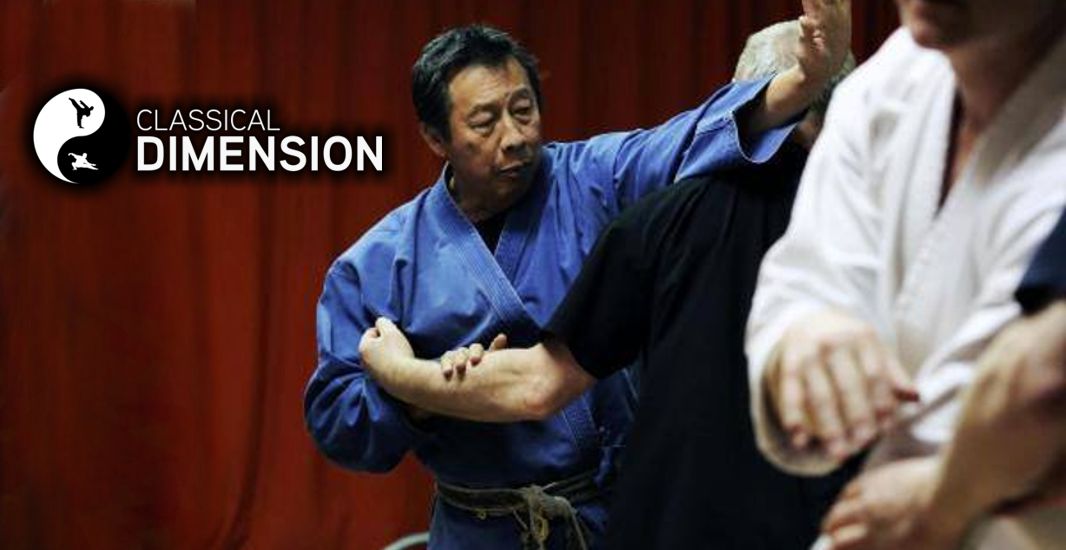

One of the main instructors to have brought Taekwon-do to New Zealand, he is now based in the USA, where he teaches his own particular versions of Tae Kwon do and Tai Chi, which he calls the ‘Classical Dimension’ or the ‘old way’ style. Loath to involve himself in any martial arts politics, Master Lim is at the forefront of a global movement to study and promote the understanding of the ‘hidden techniques’ or as he likes to refer to them as, bunkai, contained in modern striking arts.

He has, throughout his life in the arts, stretched out beyond Taekwon-do in order to help him, ironically enough, to gain a deeper understanding of the art. This has led him to train with other legends such as Taika Seiyu Oyata, the founder of Ryute Karate, George Dillman, the pressure point karateka specialist, Bill ‘Superfoot’ Wallace and Hee Il Cho, among many others.

Born into a Malaysian family of Kung fu practitioners, Master Lim actually started his martial arts journey as a student of the Japanese arts after his father, a power lifter, introduced him, when he was 14, to a famous Judoka at the time called Master Cheng Hai. Master Lim describes him as having “dabbled” in Kyokushinkai Karate, which he taught him for two years. It was not a choice that his whole family appreciated. His grandmother, a student of the Lean Wah Kun and Tai Chor Kun Chinese styles, once told him that karate was “the equivalent of a crude iron, only good for making nails.”

After seeing a physician about an injury sustained in training, he also began formally studying Tai Chi, which he has continued to train in and teach to this day.

Perhaps wary of his grandmother’s advice, his focus soon shifted away from his Japanese Karate after he saw a picture of General Choi kicking a flower pot in one of his local newspapers. After finding out about a meeting in which Taekwon-do was to be introduced to Malaysia, Master Lim promptly turned up and became the youngest member of the Taekwon-do association in the country.

The association grew rapidly in his area and was able to sponsor Master Chang Kim Choi (CK Choi) to come over to teach in Penang, after which Master Lim’s training stepped up to another level.

In order to further his education, he moved to New Zealand as a young man to attend college and then university. Along with four other students of CK Choi, he began teaching Taekwon-do in the northern half of New Zealand.

At the time, the patterns or kata were not something that Master Lim spent much time contemplating. In fact, he was not very interested in them at all, and focused his energy on sparring and competition.

“I did the patterns or kata as they were part of the syllabus but not with the same value and understanding that I place on them now,” he says.

His ‘conversion’ came about due to him suffering a period of “burn out” as he describes it, no doubt brought on by the hard work he and his peers put in trying to promote General Choi’s art in a country dominated by karate stylists. In order to freshen himself up, it was suggested to him that he invite George Dillman over to Hamilton (where he was based) to show him and his students a new perspective on the patterns or kata.

This sparked a desire in Master Lim to ensure that he and his students grew as martial artists. As a result, he brought over a number of prominent individuals from different styles to New Zealand, which already began to single him out as different from some of the other “Taekwon-do-is-the-best-style-in-the-world” instructors who were promoting the art.

Not that he was concerned about what others in the young Taekwon-do community thought of him – the standards he was responsible for spoke for themselves.

“I believe our group was responsible for improving the general standards of the martial arts community (in New Zealand),” he says. “Whenever General Choi was there in NZ, he would always use my students to demonstrate (techniques).”

Master Lim was also protected from any criticism for ‘diluting’ Taekwon-do by the General himself. “General Choi used me as a buffer against the other Korean instructors operating in my region,” he recalls.

“He supported me. I believe he did so because he could see many of the Korean instructors breaking away from the ITF when they ‘got big’. He has foreseen this pattern happening all over the globe, even before he aligned himself to North Korea.”

When it comes to discussing General Choi, and what he thought of him, Master Lim is almost cryptic in his responses. He often refers to him as the “master tactician” who was able to “manipulate the other instructors, like (he was) controlling a chess game” but he is rarely drawn into a detailed or clear answer.

“I ran my life on this theme: ‘A person can be the biggest crook to everyone, but if he is good to you, then that same feeling should be reciprocated.” He was the master controller, he was a General.

The last time Master Lim saw General Choi was in 1990 at the Montreal World Championships. He asked him how much Master Lim needed for his airfare back home and was promptly given the money, as a gesture of both respect and perhaps, affection.

Now very much apart from the various so-called official ITF and WTF bodies, which he looks upon as nothing more that “abbreviations, he believes that the strength of the instructor, his students and their respect for him is all that is important – “stronger that all the certificates from all the different organizations”.

However, he maintains that he never ‘left’ the ITF, but merely did his “own thing”. I thought that once youu were a member you were one for life, but I suppose someone needs their membership fees to be replenished every year.

As for seeing the art in the Olympics, he views the spectacle as both a step forwards and backwards. He is critical of the non realistic rules as well as the fact that in order to take part in the Olympics you have to pay your “dues” to the WTF.

It was this insular attitude that pushed Master Lim away from the formal organizations that represent the art.

In 190, he tried to introduce elements of bunkai training to some of the original pioneers, with a mind to becoming more standard Taekwon-do training but, as he explains, they were rather reluctant to take his methods on board. Whether it would disrupt their “structured syllabus” or not he does not know for sure, but he is adamant that most were unaware of the hidden applications in patterns and had little understanding of the kata bunkai.

“Anyone of us who taught bunkai in the early years, be they Karate of Taekwon-do, came down from the line of Seiyu Oyata. The truth of the matter is that many of (the early masters) never even knew this (bunkai) existed,” he claims.

So what does he think of those who call patterns or kata practice ‘dead’ timing?

“i do not eat rice, therefore you should not eat rice too, best exemplifies this attitude,” says Master Lim.

He views the patterns or katas, as ‘treasure’ maps, so by learning the fundamental alphabet of the art, students give themselves the opportunity to open up the whole ‘syntax’ of techniques that await discovery through diligent training.

What’s more, he believes there is a strong hunger to learn more through the patterns or kata bunkai. “I always find people (who want to learn bunkai),” he says.

“I have been traveling to the UK for 19 years and I have never advertised in any martial arts magazine and I have to this day not slept in a hotel all these years.”

What’s more, he is optimistic that his and others’ efforts in this still often neglected side of the striking arts will continue to grow, as more people look for answers beyond the “kick-punch’ method.

By Marek Handzel

Totally Tae Kwon Do Magazine

August 2009