As martial artists, we are unique in that we create ourselves. Through long years of rigorous training, sacrifice, denial, pain, we forge our bodies in the fire of our will. But a simple twist of fate can destroy our hard-earned bodies. All things, especially the flesh, are impermanent. Disaster can strike any of us at any time. For Great Grandmaster Al Novak, it came as a car accident.

Nearly six years ago, Al Novak’s life took a bad turn. “It was a vehicle accident,” says Novak. “My lady friend was driving. We had a blow out on two tires. Instead of stepping on the brake, she stepped on the gas. We hit a telephone poll, fireplug and the engine came up into my stomach. It took the Jaws of Life to get me out of there. Both my femurs were broken.” Such an accident would be crippling for anyone. It was devastating for a man in his eighties and left Novak wheelchair bound.

Nevertheless, Al Novak is still a force to be reckoned with in the martial world. He is present at every major martial arts event in the San Francisco Bay Area. His family and his loyal friends and students eagerly chauffeur him and all the promoters happily give him all-access passes, all out of their respect for his outstanding contribution to the field. Whether it’s Strikeforce’s Carano vs. Cyborg or our very own Tiger Claw’s KungFuMagazine.com Championship, you’re sure to find Novak there with a ringside seat. His irrepressible passion for the martial arts, exemplified by his seven decades of practice, continues to inspire us all.

Great Grandmaster Gwailo

The first Chinese immigrants called Caucasians gwailo. It began as a derogative name, but today some regard it as socially acceptable. There are many urban legends about the first non-Chinese to study kung fu in America, about how the old Chinese masters refused to teach gwailo, and about how Bruce Lee fought a duel for the right to do so. Novak refutes all that. He should know. He helped open Bruce Lee’s first Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute here in America.

Believe it or not, Al Novak began his study of the martial arts through a mail order correspondence course that he found in the back of a magazine in 1939. This was long before martial arts magazines were even on American newsstands. “It was one of those gadget magazines – Johnson & Johnson – they advertised everything,” recalls Novak. “I took the course.” Through that ad, Novak was introduced to Kano jiu-jitsu, the first in a long inventory of systems he would study throughout his life. “I studied that for a couple of years, then I went to the school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin for a year and a half.”

Soon after the start of World War II, Al Novak answered another calling and joined the Navy. Stationed in Hawaii, Novak survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. During the war, Hawaii was just a U.S. territory, not a state. Its strategic position in the Pacific made it an ideal location for military bases. Japan’s surprise attack was aimed directly at the naval base where Novak was stationed and left over 2000 dead.

At that time, Hawaii was fertile grounds for the first seeds of martial arts in America. The majority of Hawaii’s population was Asian – still is, in fact – and as always the Asians brought their martial arts culture along with them. Just as America’s East Coast became a melting pot for European cultures, Hawaii became a blend of different Asian influences. America’s earliest exposure to the martial arts came through Hawaiian-born hybrids of Japanese/Chinese styles such as Kempo (which mixed karate with southern kung fu) and Kajukenbo (which combined boxing, judo, jiu-jitsu, karate and kung fu). While these fusions are rooted in Asian cultures, they are uniquely American, thanks to Hawaii.

Being stationed in Hawaii gave Al Novak access to more martial arts than ever before, but his rise in Kajukenbo came later. Instead, Novak found a different arena in which to test his skills. “When I was in the service in Hawaii, they had a lot of jiu-jitsu by that time. They had a tavern there called Pearl City Tavern. They had a monkey bar; they had 4 monkeys. If you wanted to learn to fight, that was the place to do it. It’s been closed down about 20 years now. It’s a parking lot. When I tell old-timer Hawaiians about it, they ask, “You were there?” Yeah, I was there – for the barroom brawls.”

But the war changed everything. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Al Novak volunteered for the new P.T. Boat naval program. Short for “Patrol Torpedo,” P.T. Boats were small, highly-publicized gunboats. He was transferred to Long Island, New York. There, he wound up training alongside John F. Kennedy, but they shipped out to different seas. “He went to the Pacific. We went to the Atlantic and Normandy. We were the third ship in Tokyo Bay the day they surrendered. We stayed for over a year and a half and I got involved with Shotokan karate and Wado-kai.” Novak returned to karate in later years, after he returned to the States. It was also around then when he discovered kung fu.

But the war changed everything. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Al Novak volunteered for the new P.T. Boat naval program. Short for “Patrol Torpedo,” P.T. Boats were small, highly-publicized gunboats. He was transferred to Long Island, New York. There, he wound up training alongside John F. Kennedy, but they shipped out to different seas. “He went to the Pacific. We went to the Atlantic and Normandy. We were the third ship in Tokyo Bay the day they surrendered. We stayed for over a year and a half and I got involved with Shotokan karate and Wado-kai.” Novak returned to karate in later years, after he returned to the States. It was also around then when he discovered kung fu.

Back in America, Al Novak settled in the San Francisco Bay Area, which was becoming the next hotbed for martial arts. There was a massive influx of Asian immigrants coming into the area, and just like in Hawaii, martial arts flourished in their wake. Novak met Joe Halbuna and began training in Kajukenbo. Only three men have been recognized as 10th degrees in the Kajukenbo: Adriano Emperado, Charles Gaylord and Novak. Today, only Novak survives. It was a golden era for martial arts in the Bay Area, and Novak continued to explore more judo, jiu-jitsu, Shotokan and Wado-Ryu karate, along with Greco wrestling.

Al Novak also began studying with T. Y. Wong in the Sil Lum Fut Gar. “We used to have a school in San Francisco, 142 Waverly Place. That’s where I started with the Sil Lum system, where I took Fut Gar with Jimmy Lee. We used to go down in the basement and train. It was 1958 when I met Jimmy Lee and I started brick breaking.” Novak first saw Lee’s brick breaking demonstration at one of Grandmaster Wally Jay‘s martial arts luaus. Jay, the founder of Small Circle Jujitsu, had asked Novak to be a bouncer at his gathering.

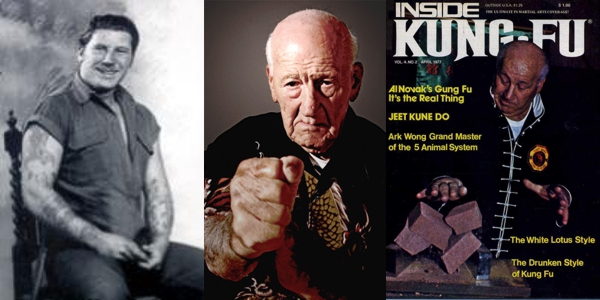

Al Novak became the first gwailo face of Iron Palm. He partnered with his teachers, and they took out small ads to advertise their program. The ad photo featured Novak smashing a stack of bricks. “We advertised in all the different magazines – Ring magazine, Popular Science. We used to advertise the brick breaking method. No one was doing that. We never used spacers at the time either. We advertised in about five different magazines. It was very successful.” The program promised to reveal how to “break bricks in 100 days.” The instructional chart cost a dollar. The book, Kung-Fu Karate, cost $5.00. It was a tiny ad, smaller than a business card, and it also promoted another book titled Bruce Lee’s Chinese Gungfu.

The Little Dragon, Bruce Lee

“When Bruce Lee first came down from Seattle, I met him,” remembers Al Novak. “He refused to fight with me. He would never fight with me. That’s documented that he wouldn’t train with me.” Given Novak’s physique back then, it’s easy to understand Lee’s reticence. Weighing in at over 300 pounds, Novak struck an imposing figure. Beyond being a Navy man, a martial arts bouncer and a barroom brawler, Novak was also a bodybuilder. In the late ’40s, he was the “Best Legs” winner at a Mr. Wisconsin competition. His Naval arm tattoos disqualified him from any of the upper body events. Yet despite Lee’s avoidance, Novak was included in the Little Dragon’s circle in those early days. “I knew Linda before they got married,” adds Novak.

“When Bruce Lee came by, that was 1962, at Jimmy Lee’s house. We started the first Jun Fan Gung Fu school in Hayward. That’s where his first school was. He was supposed to take Jimmy Lee to Long Beach for Ed Parker’s tournament. But Jimmy Lee was in the hospital, so he took one of my students, Bob Baker. So he was the uke (recipient of attack) for Bruce Lee at Ed Parker’s tournament.” Grandmaster Ed Parker is often credited as the founder of American karate and was the teacher and bodyguard for America’s first celebrity black belt, Elvis Presley. Parker’s 1964 Long Beach International Karate Championships were instrumental in introducing Lee to the growing American martial arts community. Lee demonstrated his famous “one-inch punch” technique on Baker. That demonstration rocked the martial world. It is still debated on the web today alongside grainy web video footage of the demonstration.

Despite the tales of excluding gwailo, Al Novak remembers being welcomed into the kung fu community with open arms. He became the only Caucasian master within the elite circle of west coast old school kung fu masters. “This goes back to the Northern California Kung Fu Association. We had about 18 schools involved. There was Brendan Lai, Y.C. Wong, Quentin Fong, all the old-time kung fu people. I was the only one – only white person in there.” Did Novak ever feel discriminated against? “Not at all. Everybody liked me. I got along well with the other people. I was with Brendan Lai for about seventeen years. I ran the store for him. We were business partners together. Of course, when Gini Lau came over, I got her a job in the store. She worked in the store with me. And then she was teaching at Brendan Lai’s school for a while. That goes way back many years ago.” And what about that prohibition about teaching gwailo? “I never felt it. I guess nobody else wanted to get in it at that time. I think that’s mostly made up.”

Professionally, Novak followed in the footsteps of his father. His father was a cop and was killed when Novak was about seven. “I became a police officer for 39 years, in Walnut Creek and Oakland. I also worked in San Quentin for a year and a half as a correctional officer. I was teaching self defense over there. At the same time I was teaching self defense at Castro Valley Sheriff’s Department.” While still supporting the Hayward Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute, Novak also opened his own school in nearby Niles. His East Wind Gung-fu Club was open for 39 years. He also had another school in Minneapolis, Minnesota. “Things just kept evolving from there,” says Novak wistfully.

Hurting and Healing

Over his seventy years in the martial arts, Al Novak feels the biggest changes have been the rise of wushu and mixed martial arts. “The wushu has really come up nowadays. Mixed martial arts is good. I like to watch it, but I’m a stand-up man fighter. I can’t see them laying on the ground for 15 minutes, beat the hell out of the guy and not getting hurt, you know what I mean? I don’t care for the mat stuff. It’s entertainment, but that’s as far as it goes, as far as I’m concerned.”

“Kung fu is different than wushu. I can’t do wushu. I’m not built to do wushu. I did Hung Gar and Fut Gar. We never used to kick above the waist. Even in Shotokan, we never kick above the waist. It’s all power. Back then, we didn’t hold anything back. We went full force. People got hurt. You see in the old days, if you took jiu-jitsu, you had to do what they called kuatsu. You had to be able to mend people. If you hurt people, you have to be able to mend them. Today, they have too many different versions of it now.”

Al Novak was well trained in the healing arts both eastern and western. For years, he served as the leading on-site main medic for American martial arts competitions. “I was a paramedic for about 23 years too. When I was a police officer, we had to know all that stuff. When we had these tournaments, I was a paramedic there.” So immediately after his car accident, Novak knew exactly what was going on.

“I was in the hospital for I think 13 hours. They kept asking my daughter, ‘What kind of guy is that? Where’s he from? We can’t keep him sedated.’ She said, ‘He likes pain. Don’t worry about it. He can take the pain.'” Even today, Novak’s years of conditioning have left him with skin so tough that his nurses have a hard time sticking him with a hypodermic needle. “Skin like an elephant,” says Novak with a chuckle.

“After this vehicle accident, people say, ‘You’re not yourself anymore. You’re different.’ It’s like I don’t have no sense of taste or smell. I used to have 22-inch arms. Now I have about 17-inch arms. I just lost everything. People say it’s not me anymore. I’m still here. It’s still me. You have to take me for what I am. Everybody loves me. I don’t know why. Little animals and kids, they love me. I’ve always tried to be good to everybody.”

Confidence and Commitment

“I’ll never forget the day my training started,” offers Novak nostalgically. “It’s given me a good life. That’s for sure. It’s given me a lot of confidence. I can take care of myself. As long as I was a police officer, I never shot anybody. I kicked a few people in the ass and they respected me for it. But nowadays, they’ll shoot you if you do that. Different times.”

Al Novak feels that confidence is the most important outcome of a lifetime dedicated to the martial arts. The body may fade, but the confidence remains. Despite his disability, Novak remains as self-reliant as possible. He still regularly works his way to the neighborhood bookstore by himself to peruse the latest martial arts magazines and books. For kids starting our today, he offers some simple advice. “Keep cool, mind your parents and look for a good martial arts school. You’ll get some good confidence. Build up your system and your mind.”

Al Novak is now retired and living in Fremont, California, not far from Kung Fu Tai Chi magazine’s production office. His living room walls are so cluttered with awards, certificates, banners, photos and honors that they spill over into his adjacent kitchen. Swords, knives and chain whips are strewn alongside ceremonial leis that were presented to him by the upper echelon of the martial arts. Recently, he donated all of his long weapons to a local school. Novak no longer teaches, but he still trains. “I have friends come over the house. We try figure out what it’s all about, you know what I mean? I don’t want to hurt anybody. I don’t want to get carried away. I do all my hand stuff. I got 100 lb dumbbells. I got all that stuff in the garage. People just can’t believe it. I can’t quit. That’s my life. I never quit.”

Update: We are very sad to say that Al Novak passed away in San Francisco on November 26, 2011 after being struck by a car in his wheel chair.