How many of you out there have ever wondered just how powerful a good karate spinning back fist is compared to a boxing right cross, or how deadly a muay thai knee strike is compared to a tae kwon do kick, or how fast is a kung fu finger jab compared to a boxing jab? Is it really possible for a small man to kill a large man with one carefully placed strike or for someone to easily incapacitate an attacker without throwing a single punch or kick? If there is one TV show you must see this year, it has to be FIGHT SCIENCE on Sunday, August 20 at 9 pm ET/PT on the National Geographic Channel. This highly intelligent show marries a dream team of crash test scientists, sports biomechanists and Hollywood animators with a cross-section of legitimate martial artists representing various styles of martial arts in an attempt to separate martial arts fact from fiction.

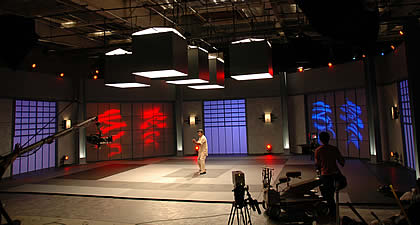

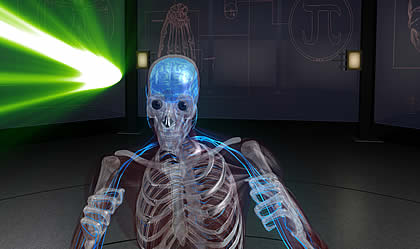

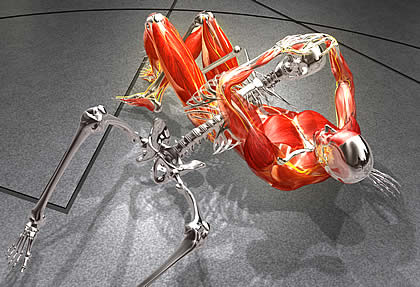

With 32 infrared motion capture cameras, three high-definition cameras and three ultra-high-speed cameras carefully utilized throughout a custom-built combination dojo, high-tech lab and film studio that took over a year to design and build, scientists used crash test dummies to measure and map speed, force, range and impact of muscles and bones on the fighter’s body. Furthermore, by using motion-capture techniques and CGI animation, various sophisticated animated models of the human musculo-skeletal, nervous and organ systems were created to gain insight into just how the body generates each move and what the effect is on the human body when subjected to these attacks. What all of this really comes down to is that for the first time we are going to scientifically determine just how fast and powerful martial artists’ punches and kicks are, and to answer all of the aforementioned questions. To me, this is one of the coolest shows ever on TV that deals with martial arts outside of cinema.

© 2005 BASE Productions, Inc. Photographer: Mickey Stern

“The first thing to clarify here is that this is not about comparing styles or trying to prove one style is better than the other,” the show’s producer and martial arts supervisor James Lew asserts. “To me this is hopefully a way to unify all styles and to develop an understanding of the techniques of these styles with the further purpose of quantifying the martial arts.

“We have always been struck with the mystery of martial arts, train traditional ways, never question, just do it until it works. But personally, I have always been interested in finding out how fast and powerful a technique is. Also with this show, the general public can relate to the martial arts, as we are able to demystify them and make people understand that what we as martial artists do takes hard work and discipline.”

The martial artist test subjects that FIGHT SCIENCE put under the gun includes the 200-bout tae kwon do champion Bren Foster; leader of the Gracie clan Rickson Gracie; stuntman and karate expert Mark Hicks; the legendary Danny Inosanto; the only female subject and former Beijing Wushu Team member Li Jing; veteran ninjitsu practitioner Glen Levy; the proclaimed “world’s greatest grappler” Dean Lister; muay thai world champion Melchor Menor; seven-time Japan national cutting champion and descendant of the Heike clan samurai line Obata Toshishiro; undefeated pro-boxer Steve Petramale; holder of seven world records for breaking ice, brick walls and cinderblocks Craig and Paul Pumphrey; senior disciple of Toshishiro and weapons expert Nathan Scott; the founder and leader of Capoeira Los Angeles Amir Solsky; and, representing kung fu and wushu, three-time national gold medalist in wushu, Shaolin kung fu stylist (dragon fist) and Chinese kung fu weapons expert Alex Huynh.

“I was humbled with the caliber of the talent that was on the show,” Huynh admits, “and I was excited to get involved in this project as it is a cool concept to merge these two different worlds of science and martial arts. I also thought that this would be a great training tool, and I really wanted to know just how fast I was, and if I wasn’t fast enough with the numbers, then I must train harder.

“When I found out I was four times faster than a snake (rattlesnake),” he youthfully laughs, “I was like let’s go out and get a snake and challenge it. It was amazing working with these scientists.”

Who were these champions of science that put all of these dedicated martial artists to the test? Dr. Cynthia Bir from Wayne State University and creator of what she calls “the three-rib, ballistic-impact device,” a human-shaped gel dummy used to evaluate the impact of bullets and edged weapons and assess their injurious effects on the human body; Dr. Tim Walilko, senior engineer at Applied Research Associates and trauma and sports biometrics specialist; Dr. Norman Murphy, a biomechanist at Tekscan, Inc., with expertise in using an in-shoe F-Scan sensor to instantaneously map and track the human gait and balance in real time; and Randy Kelly, engineer and VP of sales and business development at Robert A. Denton, Inc., the world’s leader in the design and development of government-approved crash test dummies, the martial artists’ main opponent in the FIGHT SCIENCE ring of knowledge and technology.

“To be honest, I have never had an interest in martial arts,” Kelly admits, “and so our interest in FIGHT SCIENCE is that we are always looking for ways to understand the impact on human bodies, and this was an avenue to collect data in a field we’ve never done before and to see what we can learn about their punches, kicks, power, speed and balance. Can they administer the death punch? More kids are involved in martial arts than ever, and we wanted to understand what is happening in martial arts and if we need to incorporate any safety features to make this a safe activity.”

When asked if the scientific team had any expectations or skepticism in regard to what we hear about martial artists and their abilities, Kelly says, “Because I come from the crash environment, which is a pretty severe application, we typically run our crashes at 30 mph, 35 and higher; I wasn’t expecting much in terms of sheer power or force. Also, because our crash test dummies and sensors are designed for high impact, I didn’t expect any of these guys to register much of anything that was significant.”

One by one each stylist stepped up to the dummy and gave it their best punch and their best kick. Some martial artists were finally able to let loose with their deadliest techniques, from ninjitsu expert Glen Levy’s “kill with one strike” blow to Rickson Gracie being able to apply the full force of his family’s devastating joint locks and neck twists. Additionally, various weapons such as the Chinese broadsword and straightsword (jian and dao), the samurai sword, nunchaku, 3-section staff, bo and kali sticks were all evaluated in terms of their potential for inflicting bodily harm and quickly killing an assailant. One special test using ninja plum poles (poles of varying heights arranged in patterns for movement and stance training) investigated whether some martial artists could jump and walk with the stealth of a cat. It was also determined just how much force was needed to break through blocks of ice, cinderblocks and bricks, and if these breaks were for real or simply based on tricks of physics.

“On the first day of the show there was a lot of egos running around,” Kelly reflects. “There was also a sense of pride with the people on what they could do, but not boastful, more of, ‘Wow, I have data to justify what I’ve always thought.’ For example, you can see the ninja guy (Levy) get excited that he could displace the sternum enough to cause death. The muay thai guy (Menor) knew his knee was powerful, but he had no way to judge it other than the guy on the floor.”

Lew agrees that in the beginning each martial artist was sort of giving each other the eye, measuring each other up, but as time went by the true magic of martial arts shone through: brotherhood.

“The mutual respect came out,” Lew says, “and each was interested to watch the other perform. So again it was a fantastic way to unify the martial artists. We can all appreciate something that is done so well, regardless of what style, because you can see the true artist of that style. We became like one happy family and that was the coolest thing.

“To me, another gift of the show was when Menor, who earlier was very spirited with his knee strikes, got to do the ninja plum poles. His attitude was like, ‘I’m going to go up there and show everyone what I can do,’ but when he got up there, he was shaking in fear. I got a sense that it was a humbling experience for him, and what he took away from the show was that, ‘I may be a great fighter, but I still have a lot to learn.’ It’s true, the statement about the more you know the less you know. As I was watching everything go down, I realized that I am only touching the tip of any of this knowledge.”

For Huynh, and undoubtedly for most of the martial artists, there was probably a seed of doubt in their minds as to whether or not they were representing their respective arts in a positive light and in a fashion that reflects well within the community of their style. Yet at the end of the day, Kelly, whose job as a scientist is to look at things in an objective manner emphatically stated, “The tests revealed a fair assessment of each of the martial arts, and what we can say is that, given that particular series of tests, and those individuals striking those crash test dummies, certain martial artists had the most effective kick or punch or strike on that particular day. We now have data to quantify these things.

“What was great about the show was that although we were able to point out the strengths and potential weakness of each style, it was not about showing which style is good or bad. The program did a good job of highlighting their differences in techniques and that size makes a difference. They showed the human anatomy so well and did a good job of explaining what happens to the human body when struck.

“We would like to test other martial art disciplines, get a broader data base and also use martial artists with similar size and mass to get a better A to B comparison. We’d also use a different dummy because the one we used had too much rebound during impact. If we had braced the dummy more, we would probably have seen higher punch and kick loads than what we presented on the show.”

Huynh notes, “During the weapons portion, where they used ballistic gel to create the feel of thrusting a sword into a human body, I thought it would be a piece of cake to cut it up. But when I felt the gel in front of me and the camera was rolling, something inside of me clicked; because I had never cut a person before, besides myself during practice, and now this is an opportunity to cut someone with a sword and it would feel real. It was a moment of fear. But the director came up to me and said, ‘Relax, it’s not real.’ I’m thankful to James for giving me the chance to represent the kung fu/wushu community. To me, martial arts in the broadest sense is the destination, and the styles are the avenues to this destination, and to understand martial arts as a whole you have to understand each discipline.”

Following the results of all of these experiments, two things stuck out in my mind which I will relate in a humorous tone. First, I am glad no one in the world is the master of every martial art; second, thank god we don’t stand still when we get hit.

Lew is a believer in cross training, saying that by learning and training in many different styles, you can improve your own style. The results of these tests prove the capabilities and gaps in knowledge of each style. Similar to Kelly’s conclusion about the show’s value, Lew agrees that the data should be used to develop better protective sparring gear and pads that can more efficiently dissipate a strike’s power, eliminate the damage and minimize the injuries.

On a personal note, though, Lew was impressed by the singularity of a boxer’s punch and with the technology of speed sensors, saying, “It’s a great way to learn how to hit harder and faster. They put a sensor in your hand and you punch. It then measures speed from point zero, midway and at the point of impact. So they can measure if you’re slowing down through your punch, which of course will affect the punch’s performance.”

Although on a “wow”-factor basis Kelly was impressed with the breaking abilities of the Pumphreys (during the wall-breaking segment, when the wall was three quarters built, the Pumphreys insisted on tearing it down and rebuilding it because they found a cracked brick), it was the intangibles that Kelly appreciated most about the martial artists.

“With the weapon users, it was amazing that when they used the weapons, they truly were extensions of the hand,” Kelly says. “But the one thing that impressed me most about them was everyone’s sheer athleticism, their commitment to their discipline and that they were all very smart about the human body on what it is they could and could not do. But overall, they were all just great people. Like the martial arts spirit, it is these things that can’t be measured scientifically.”

Fight Science was executive produced by John Brenkus and Mickey Stern of BASE productions.

Written by Craig Reid for KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM © COPYRIGHT KUNGFUMAGAZINE.COM, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

All other uses contact us at gene@kungfumagazine.com.